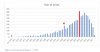

I can think of a number of possible explanations as to why the study finds a steady increase in the onset of ME/CFS, since the mid-80s to around 2015. But I am keen to hear others.

My starting point is that I expected to see a fairly flat graph. Apart from any epidemics that produced the spike in cases, I'd assumed that there would be fairly constant number of new cases every year. (While it's likely that people who have recovered wouldn't take part in the survey, the

Cairns review of recovery found that it is rare.)

1. Increase in diagnoses.

Certainly in the UK, CFS has become much more common diagnosis since around 1990, when proponents of psychosocial theories encouraged its diagnosis, and "treatment". Perhaps there was a similar trend in Norway, but it would have to be a steady trend of increasing diagnosis (perhaps as awareness slowly increased among Norwegian doctors).

2. Underrepresentation of older people (who will generally have onset earlier in time).

Those with an onset earlier in time will, on average, be older than those with a more recent onset. If older people are less likely to use social media/access the survey, that would lead to increasing underrepresentation of people whose onset is further in the past. And so produce the effect of fewer cases further back in time.

3. A fairly steady rate of recovery from ME/CFS over time.

This strikes me as the simplest explanation. However, it doesn't fit with what we know about the illness (either from the Cairns study or anecdote).

The second point is testable. If we look at the 1990s, for instance, and assume that there is underrepresentation of older people who got ill in that decade, then the average age of onset (of those represented in the study) would be younger than for recent decades. (Someone who got ill aged 40 in the 1990s will be considerably older than someone who got ill aged 20 in the same decade.)