Sly Saint

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

A mass disabling event: The effects of long COVID don’t stop at the individual

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines long COVID as those experiencing ongoing symptoms lasting at least two months after their COVID infection. Dr. Aurora Pop-Vicas, associate professor of Medicine (infectious disease) at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health and a UW Health infectious disease physician, told Daily Kos that long COVID is a “general term with a large umbrella encompassing many clinical manifestations. One person doesn’t have everything.”

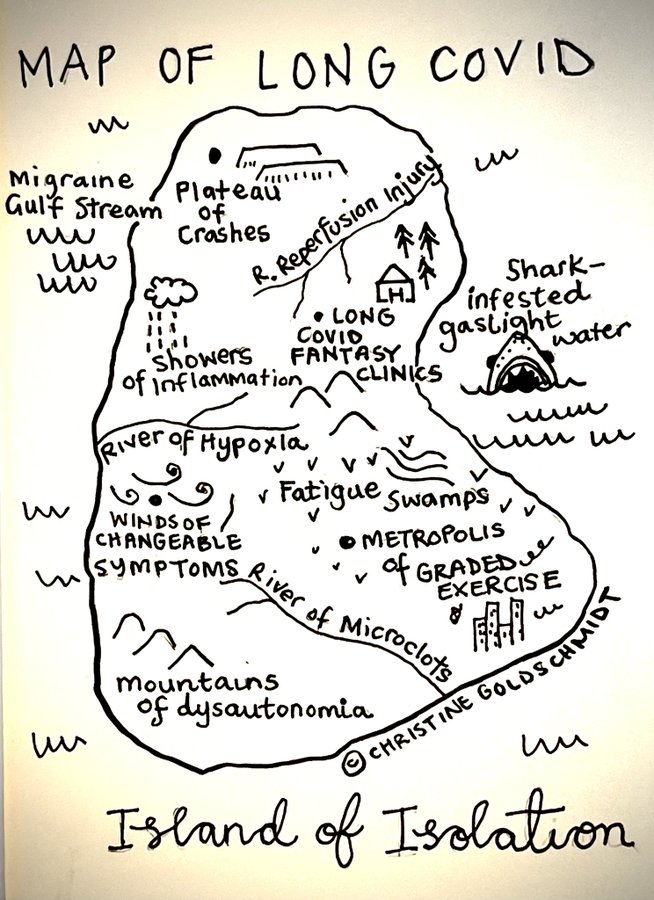

She divided symptoms into three categories, elaborating, “the most common cluster is around chronic pain, chronic fatigue, and maybe rash or skin manifestations. And then, there is a cluster around mood disorders, exacerbated anxiety, depression, insomnia, and cognitive decline, the so-called brain fog. And the third class with more common manifestations such as chronic cough, shortness of breath, and phlegm production.” Dr. Pop-Vicas emphasized a significant overlap between the clusters and other post-infection illnesses.

The exact number of people with long COVID will fluctuate. Most people will fully recover over time, but many will not. What do we know? The exact percentage is hard to pin down because this is a new phenomenon; according to the Solve Long Covid Initiative, an enterprise out of Solve M.E., 10-30% of people with a COVID infection will develop long COVID. (Solve M.E. is a non-profit organization working to deepen research and treatment for post-infection diseases. M.E. is short for Myalgic encephalomyelitis, better known as chronic fatigue syndrome [CFS].)

Solve Long Covid Initiative classifies people with long COVID into two groups, “Long Covid (LC) and Disabling Long Covid (DLC).” The former are those who fully recover after sustained symptoms; the latter are those who never fully recover.

https://www.dailykos.com/stories/20...-t-stop-at-the-individual?utm_campaign=recentLong COVID presents a unique opportunity to study post-infection illness in real-time. Ideally, there would be a massive federal government investment into studying how post-infection illnesses come about, their duration, types, biological markings (something that could show up in a blood test), and treatment. In addition to an overhaul of disability infrastructure, there needs to be better and more flexible support for people on the spectrum of disability. With millions of people already having experience with long COVID, this could become a mass disabling event. This could push even more people out of the workforce entirely, with millions more reducing economic participation while increasing their needs for medical care.