9) Minimally important differences

I’ve been reading up on the issue of minimally important differences (MID), the smallest difference that patients are likely to consider important. The authors of the Cochrane review have used MID to suggest that the treatments effects they found are clinically relevant.

There are basically three methods to estimate MIDs. There’s the distribution method which estimates MIDS based on easily available figures such as the standard deviation. There’s the anchoring method where scores on a questionnaire are compared to an ‘anchor’, another measure whose score is easily interpretable. Thirdly, there’s a quantitative measure where patients, clinicians or experts are interviewed directly on what they think the MID is.

Fatigue

For the 33-point Chalder Fatigue Scale (CFQ) Larun et al. refer to a lupus study (Goligher et al. 2008) that found a MID of 2.3 points. It used the anchoring method that went along these lines. First lupus patients filled in the CFQ. Afterwards they had a 10 minute discussing with another patient about their fatigue. They then had to estimate how the other patient’s fatigue relates to theirs on a 7-item response scale going from: “Much more fatigue,” “Somewhat more fatigue,” “A little bit more fatigue,” “About the same fatigue,” “A little bit less fatigue,” “Somewhat less fatigue,” to “Much less fatigue.” This way the authors could estimate scores on the CFQ correspond to the responses given on the 7-item scale. They can then estimate the MID by looking at the difference in CFQ scores between “About the same fatigue,” and the other responses and using regression analysis. Two other studies have used the same approach to estimate MID for the CFQ, one also in lupus patients, the other in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Their estimates are similar, in the range 1.4-3.3 (It’s difficult to abstract the right data from the paper but I think these are the relevant figures),

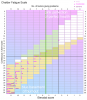

There are however some problems with this approach. If a questionnaire is insensitive to severity of fatigue (for example if it does not give a strong difference in scoring between someone who is mildly fatigued and someone who is severely fatigued) then the scores corresponding to a difference between responses “About the same fatigue” and “A little bit less fatigue” will look small. Consequently, the MID will also be small. I think that might be what happened with the CFQ because in the three studies MID were calculated for multiple questionnaires and in all three cases the standardized MID (the MID divided by the standard deviation) was the lowest for the CFQ. If one looks at the graphs that give the mean CFQ scores for the 7 responses, one can see that there’s quite a lot of overlap. Sometimes the score difference for “About the same fatigue,” is higher than for “A little bit less fatigue”. So the method is certainly not perfect (I suspect the data from these studies is interesting for those wanting to analyse the CFQ).

I think Nosthal et al. 2018 used a better approach. They handed out the CFQ to persons who were about to have a surgery and they let them fill in the questionnaire at different time points after the surgery until their recovery. Each time the researchers added the question: “Given your current description of fatigue; would you say it has been of considerable significance to you?; Yes/No”. This way they could estimate which CFQ score corresponds to a yes to this question. On average this was a score of 15.1. Because the baseline score was 11.7, I think the study indicates that an increase of 3.4 was the minimal significant difference.

Then there’s the letter by Ridsdale et al. 2001., where they proposed a MID of 4 points. They have used this threshold in a 2012 economic analysis of a study of GET and counseling for patients with chronic fatigue. Although Trudie Chalder en Simon Wessely, the creators of the CFQ, were not listed as authors on the letter, they were part of the study that Ridsdale et al. were defending. So I think it’s reasonable to assume that they were included in the consensus view Ridsdale et al. referred to. The full quote is as follows: “The researchers in this trial include several of those involved in developing and testing the instrument. Our consensus view was that a difference of less than four, using a Likert scale, is not important.”

Finally there’s the PACE trial (of which Chalder is an author) where a distribution approach was used. They took half the standard deviation and came up with a MID of 2. There were some problems with this approach though. The CFQ was used in the selection criteria of the sample so the SD was probably reduced. I think the standard deviation of the 33-point CFQ is usually somewhere between 5 and 6 points, so a distribution estimate of the CFQ would come up with a MID of 2.5-3 if done correctly. It also seems that the MID used in the PACE trial was a post-hoc measure. Originally the authors were going to use the 11-point version of the CFQ and regard a 50% reduction or a score lower than 3 as a ‘positive outcome’. The baseline score on the 33-point version was approximately 28 points. Even if we take 11 points as the bottom of the scale, a 50% reduction would still mean a reduction of 8,5 points on the CFQ. Even though they planned to use the 11 point version, I think it’s clear they initially had a larger point reduction in mind to measure improvement.

In conclusion: the MID estimate used by Larun et al. is not way off from other estimates, although none of these have asked patients what they would consider a MID. The 3.4 point difference found in the meta-analysis is very small, close to the MID and even lower than some estimates.

View attachment 8766

Physical functioning

I think the conclusion is similar for the SF-36 physical function (scale 0-100), where the authors have used a MID of 7 points. It’s a bit on the low side but perhaps not unreasonable. The PACE trial used a MID of 8 points for SF-36 physical function, which was half the standard (SD) deviation in their sample. But as they used the SF-36 as a selection criterion their SD was lower than in an unselected sample. In the observational study by Crawley et al. the SD for physical function at baseline was 22.7 which would result in a MID of 11.35. The GETSET protocol also used a MID of 8 points.

Crawley did a study on the MID for the SF-36 on adolescent CFS patients, just last year (Bridgen et al. 2018). They came up with a MID of 10 points. This actually looks like a decent study, as they used both the distribution, anchoring and qualitative method. They took “qualitative interviews” with 21 young CFS patients and their parents to see what they would find a MID. A MID of 10 was used in the FITNET-NHS protocol and the Lightning process economic analysis.

Estimates from other patient groups are in the same range. Wyrwich et al. 2005 used a Delphi technique, a process where experts come together to reach a consensus on something. The result was a MID of 10 points on the SF-36 physical function scale for patients with heart or lung disease. But two years later Wyrwich et al. used the anchoring method on patients and GP’s and they came up with lower estimates. So that’s one of the papers Larun et al. refer to for using a MID of 7. The other reference they list is a 2014 study (Ward et al. 2014) on patients with rheumatoid arthritis that used the anchoring method to come to a MID of 7.1 points. I’ve found a study on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (Witt et al. 2019) that found higher estimates (range 10.1-22.2) but there’s another study on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis that came up with a much lower MID of only 3 points (Swigris et al. 2010). A study on prostate cancer survivors (Jayadevappaet al. 2012) came up with a MID of 7 points.

View attachment 8767

In conclusion: the post-treatment point difference found for the SF-36 physical functioning in the Cochrane meta-analysis was 13.1. But I think that’s a distorted figure because of the outlier of Powell et al. which reported an implausible difference of 31.75 points. If this study is excluded the mean difference drops to 7.37 which is close the MID used and even lower than some MID estimates.

References

Goligher et al. (2008).

Minimal clinically important difference for 7 measures of fatigue in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Pouchot et al. (2008).

Determination of the minimal clinically important difference for seven fatigue measures in rheumatoid arthritis.

Pettersson et al. (2015).

Determination of the minimal clinically important difference for seven measures of fatigue in Swedish patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Nøstdahl et al. (2018).

Defining the cut-off point of clinically significant postoperative fatigue in three common fatigue scales.

Ridsdale L, et al. (2001).

Chronic Fatigue in general practice: authors reply.

Bridgen et al. (2018).

Defining the minimally clinically important difference of the SF-36 physical function subscale for paediatric CFS/ME: triangulation using three different methods.

Wyrwich et al. (2005).

A comparison of clinically important differences in health-related quality of life for patients with chronic lung disease, asthma, or heart disease.

Wyrwich et al. (2007).

A comparison of clinically important differences in health-related quality of life for patients with chronic lung disease, asthma, or heart disease.

Ward et al. (2014).

Clinically important changes in short form 36 health survey scales for use in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials: the impact of low responsiveness.

Witt et al. (2019).

Psychometric properties and minimal important differences of SF-36 in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis.

Swigris et al. (2014).

The SF-36 and SGRQ: validity and first look at minimum important differences in IPF.

Jayadevappa et al. (2012).

Comparison of distribution- and anchor-based approaches to infer changes in health-related quality of life of prostate cancer survivors.