10) Harmful effects

I also had a look at possible harmful effects. Next to fatigue, this was the primary outcome of the review. Larun et al. have downgraded the quality of evidence for this outcome to very low quality (the lowest rating) because there was too little data to form any conclusion. Only one study, the PACE trial, has reported on the rate of serious adverse reactions (SAR) between exercise therapy and treatment as usual. It reported 2 events in the intervention and 2 in the control group. Larun et al. have downgraded the quality of evidence with two levels for imprecision and notice that “this available trial was not sufficiently powered to detect differences this outcome.”

A closer look at the safety data from the PACE trial

There were more serious adverse events (SAE) in the GET group (17 in total) than there were in the SMC group (p=0·0433), (only 7 in total). That could mean two things: (1) that there happened to be more serious adverse events in the GET by coincidence and that these had nothing to do with the therapy or (2) that there was a problem with the judgement of the raters who might be unwilling to attribute a deterioration to treatments. The PACE-trial said the raters were blinded to treatment allocation, but they might be aware that not attributing serious adverse events to treatment would make GET and CBT look safer. After all, there weren’t many people claiming that APT would be harmful, and this was certainly not the case for SMC. Safety was suspected to be an issue for GET/CBT. So in a way, the raters could not be fully blinded to the trial hypothesis that GET and CBT would be safe and effective treatments. If you look at the description of the 10 SAR in the trial, most were related to depression, suicidal thoughts or episodes of self-harm. That seems to suggest that the raters were very reluctant to attribute a deterioration of physical health to the treatments. This only happened 5 times in a sample of 641 patients!

You could argue that few serious adverse events indicate that the treatments were safe, but SAE was defined quite strictly. It involved either death, a life-threatening event, hospitalisation, a new medical condition or - and this was probably most relevant to the trial - “Increased severe and persistent disability, defined as a significant deterioration in the participant’s ability to carry out their important activities of daily living of at least four weeks continuous duration.” This was determined by people involved in the trial such as a research nurse or centre leader. 4 weeks is long but given this description, I would suspect that more patients would have experienced such an episode. For example, it happened only 8 times in the 161 patients in the CBT group. Even if no treatment was offered and it was just the natural course of the illness, I would suspect that more patients deteriorated in this way.

The PACE trial also had data on non-serious adverse events, but these were so common that they probably mean very little to the safety of GET. Just about every patient had a non-serious adverse event during the trial. What we would be interested in is something between a non-serious and serious adverse event: something that gave enough data on deterioration without becoming trivial.

The PACE trial did have some other indicators of deterioration such as a decline of 20 points for physical functioning or scores of ‘much worse’ or ‘very much worse’ on the PCGI scale, but the authors required this to be the case for two consecutive assessment interviews. As Tom Kindlon explained in

his excellent commentary, this is not the case in the protocol where they speak of a deterioration compared to the previous measurement. The changes were not explained in the text and the protocol-specified outcome was never reported. That makes me a bit suspicious…

The others trials

In the other trials harms were not particularly looked at as an outcome. They only way patients could indicate deterioration was in the main outcome measures. There were some trends in some cases but I don’t think any of the outcomes measures used in any of the GET trials indicated a statistically significant deterioration in the GET group compared to the control group. Some trials used the clinical global impression scale where patients could indicate they got ‘A little worse’ (score 5) ‘Much worse’ (score 6) or ‘Very much worse’ (score 7). In Fulcher & White 1997 only one out 29 participants in the GET group give a score of 5, none gave a higher score. The same was true for the Wallman et al.2004 trial. In the Moss-Morris et al. 2005 trial, this was measured but not reported. The clinical global impression scale was used but they only looked at the improvement scores. The Jason et al. 2007 study had patients and clinicians rate overall improvement but they combined the scores for deterioration with these of ‘no change’. The percentage of patients in this category for the GET group was between 52-59%. I think this indicates how poorly these trials reported possible harmful effects of GET.

One reason patients might fail to report harms of GET is that they are not blinded and reporting deterioration might make the intervention and thus the trial, the researcher or the therapist, look bad. Another reason is that the GET-manuals and instructions were quite assertive in telling patients that GET is safe (normally that would be the objective of doing a trial, not something you tell patients at the beginning). The booklet that was used in the FINE and Powell et al. 2001 trial said: "Activity or exercise cannot harm you. Instead, controlled gradually increasing exercise programmes have been used successfully to build up individuals who suffer from CFS.” The PACE trial manual said: “there is no evidence to suggest that an increase in symptoms is causing you harm. It is certainly uncomfortable and unpleasant, but not harmful.” Other sections of these manuals try to convince patients that their symptoms are due to deconditioning, stress or anxiety and that interpreting them as signs of disease may worsen outcomes.

Drop outs

Some have argued that drop outs should be seen as a measure of safety and harm. The (previous) Cochrane handbook advises to be cautious with such interpretations because there are other reasons why patients might drop out than safety: “Review authors should hesitate to interpret such data as surrogate markers for safety or tolerability because of the potential for bias.”

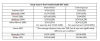

The table below gives an overview of the dropouts in all the trials. In the two Wearden trials and the Powell et al. 2001 trial there was a higher dropout rate in the GET groups compared to controls. But this wasn’t the case in the other trials and the overall test for overall effect gave a non-significant p value of 0.2. In the trial by Moss-Morris et al. 2005 a lot of patients refused to do the exercise test but the same was true in the control group.

EDIT: the graph has been updated to include the drop out of Wallman 2004

I’ve played a bit with the data. If the PACE trial was excluded from the Cochrane analysis, things change a little and the p-value comes close to significant (0.05). There’s also an issue that the FINE Trial is given a very low weight because it had no dropouts in the control group. If more patients had dropped out in the control group that would paradoxically increase the risk ratio for the entire analysis. On the other hand, the trial by Jason et al. 2007 was not included because it doesn’t give exact drop out figures. It did say the drop out was around 25% with no significant difference among the groups. The drop out in Wallman et al. 2004 was also not included, although it was higher in the control than in the exercise group (It is rather weird that in this trial, no participants dropped out during treatment, only during baseline testing). Overall, I don’t think there’s a statistically higher dropout rate in the GET group in this analysis.

Intention to treat or available case analysis?

Finally, from the email correspondence we know that one editor raised an issue about the dropout rate. Atle Fretheim explains in an email dated 29 may 2019:

“The co-editor also claims there is a problem with the data in a table since for some studies the “N” (total number of participants) minus the drop-outs does not add up to the “n” (number of participants included in the analyses). The explanation is straightforward: In intention-totreat analyses you include participants to the extent that you have usable data, including for drop outs. There is also some variation on how this is done across the various studies. This is also described in the Cochrane Handbook (16.2.1. Introduction to Intention to treat analysis). Consequently, we reject both this points of criticism.”

It seems that the (old) Cochrane handbook says there are two options: available case analysis where you report all the data you have and count each participant in the group to which she was randomized. The alternative is an intention to treat analysis where you analyze all randomized patients and impute data on participants where you don’t have any. The Cochrane handbook suggests that it’s a matter of opinion and judgment what is considered the best approach. They write: “Although imputation is possible, at present a sensible decision in most cases is to include data for only those participants whose results are known, and address the potential impact of the missing data in the assessment of risk of bias.” So my first impression would be that the authors have a point here. Would be interested to hear what others think.