You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

News from Germany

- Thread starter TiredSam

- Start date

-

- Tags

- germany me/cfs news regional thread

Considerable visibility as noted by Solstice. Plenty of patients, family members and a couple of medics responding very positively in the YouTube comments (360,000 views, 2500 comments currently). Two auto-translated medical comments I noticed —

I am a family doctor and often feel helpless. The colleagues often tell the patients so much nonsense and present them as simulating hypochondriacs. You can do so little proven helpful, it is with each patient an individual try what helps and does good. The evidence is simple, except for a few things, pacing, avoiding crashes still so deficient. Rehabilitation can hardly be recommended for the reasons mentioned, but the payers push for it for a long period of time. Just like with physiotherapy, presentation to specialists, the medical principle of not to harm at first, is unfortunately often not followed and the patients suffer. Thank you for this post.

As an internist, I find it frightening when a professor of neurology explains symptoms as the cause or even the diagnosis of a disease. Where did he study medicine and why is he allowed to teach?

I am a family doctor and often feel helpless. The colleagues often tell the patients so much nonsense and present them as simulating hypochondriacs. You can do so little proven helpful, it is with each patient an individual try what helps and does good. The evidence is simple, except for a few things, pacing, avoiding crashes still so deficient. Rehabilitation can hardly be recommended for the reasons mentioned, but the payers push for it for a long period of time. Just like with physiotherapy, presentation to specialists, the medical principle of not to harm at first, is unfortunately often not followed and the patients suffer. Thank you for this post.

As an internist, I find it frightening when a professor of neurology explains symptoms as the cause or even the diagnosis of a disease. Where did he study medicine and why is he allowed to teach?

Nightsong

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

This article just appeared in my news feed ("Post-COVID Syndrome: Government-funded drug study gets underway"):

https://aktuelles.uni-frankfurt.de/...e-government-funded-drug-study-gets-underway/

It relates to a trial of vidofludimus, which is a dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor previously trialled in MS & which has also apparently been trialled in acute SARS-CoV-2 cases.

https://aktuelles.uni-frankfurt.de/...e-government-funded-drug-study-gets-underway/

It relates to a trial of vidofludimus, which is a dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor previously trialled in MS & which has also apparently been trialled in acute SARS-CoV-2 cases.

Dolphin

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Cases of Long Covid still growing, German health minister says

(Has some references to ME/CFS)

https://www.yahoo.com/news/cases-long-covid-still-growing-151626706.html

(Has some references to ME/CFS)

https://www.yahoo.com/news/cases-long-covid-still-growing-151626706.html

rvallee

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

So, yesterday a public roundtable was held, lead by health minister Lauterbach, discussing Long Covid and the publication of a list of off-label medications that MDs can consider prescribing. There was some mention of ME/CFS, but one controversial decision so far is that non-COVID ME/CFS, or non-COVID any chronic illness really, is excluded. Since LC is typically defined saying a validated test is not necessary, given the general clusterfuck state of things, I don't know how they'd discriminate beyond pre/post 2020. Which would still allow some non-COVID chronic illness. Bit of a mess.

Article covering the gist: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/nachrich...tierten-Behandlung-von-Long-COVID-vorgestellt, which includes some discussion of ME/CFS: "The round table also pointed out clear deficits in the care of patients with long COVID and similar illnesses or ME/CFS, despite all the progress". Not sure what "all the progress" means here. There's been exactly zero progress because it's held back by a medical profession that simply refuses to budge from its traditional myths.

The document listing the medications and describing their use: https://www.bfarm.de/SharedDocs/Dow...l/Zulassung/ZulRelThemen/therapie-kompass.pdf.

The list, fortunately no knowledge of German needed to know what they are:

Article covering the gist: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/nachrich...tierten-Behandlung-von-Long-COVID-vorgestellt, which includes some discussion of ME/CFS: "The round table also pointed out clear deficits in the care of patients with long COVID and similar illnesses or ME/CFS, despite all the progress". Not sure what "all the progress" means here. There's been exactly zero progress because it's held back by a medical profession that simply refuses to budge from its traditional myths.

The document listing the medications and describing their use: https://www.bfarm.de/SharedDocs/Dow...l/Zulassung/ZulRelThemen/therapie-kompass.pdf.

The list, fortunately no knowledge of German needed to know what they are:

- Antidepressiva (Amitriptylin, Bupropion, Doxepin, Duloxetin, Mirtazapin, Sertralin, Vortioxetin)

- Aripiprazol

- Betablocker

- Glukokortikoide

- Ivabradin

- Metformin

- Midodrin

- Naltrexon

- Nirmatrelvir / Ritonavir

- Pyridostigmin

- Statine

Last edited:

rvallee

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

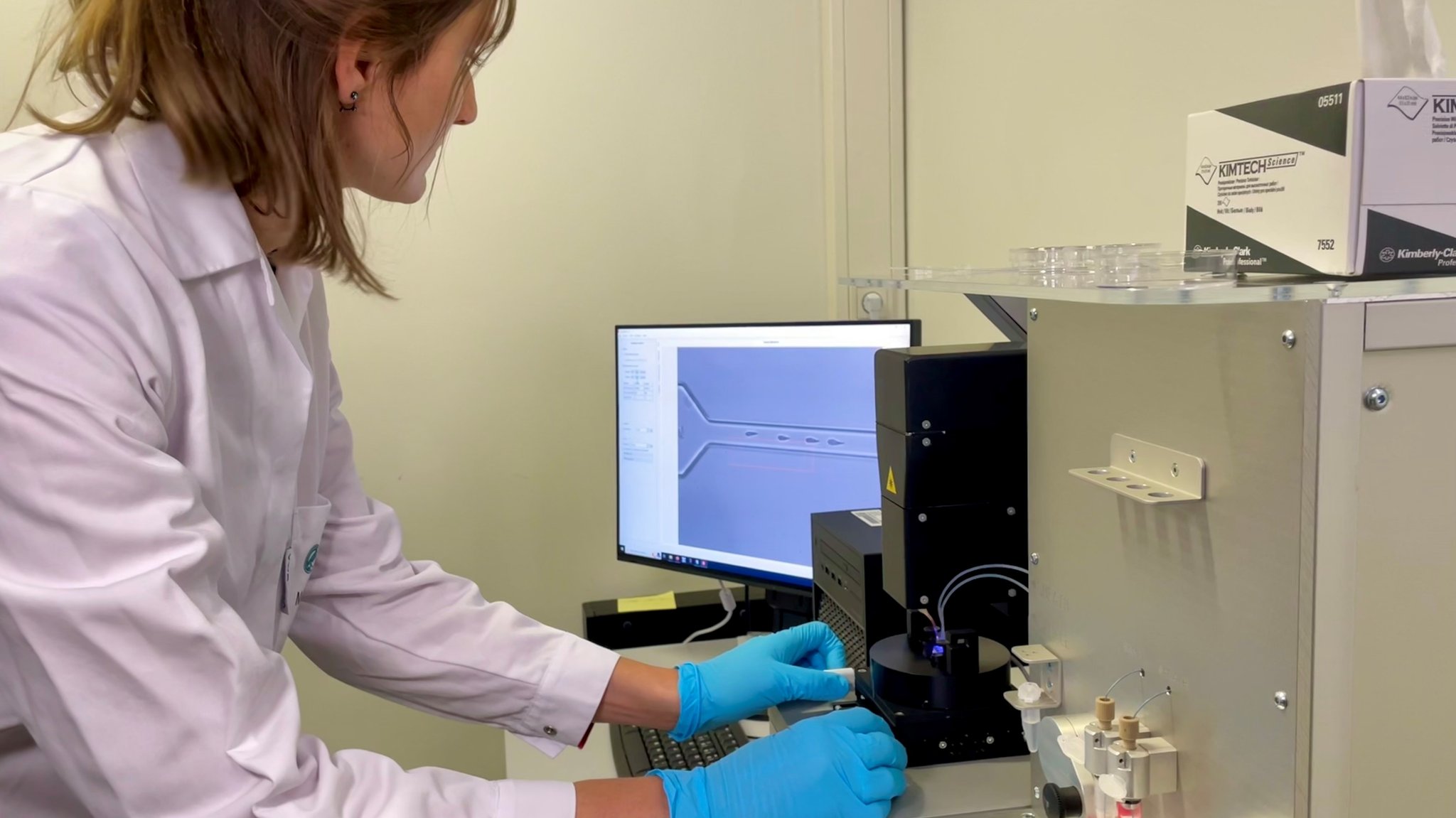

Making Long Covid measurable: New Max Planck Center opens

https://www.br.de/nachrichten/wisse...en-neues-max-planck-zentrum-eroeffnet,UOXB90O

Close to the university hospital and therefore close to the patient: The new Max Planck Center in Erlangen is intended to facilitate the exchange between basic research and medicine. The new building has now been opened, where research into long Covid is also being carried out.

...

The blood samples collected since 2021 are currently being analyzed. However, there are no initial results yet. "If everything goes well, we will know in six months whether we have a chance of seeing differences between long-Covid patients and healthy subjects."

https://www.br.de/nachrichten/wisse...en-neues-max-planck-zentrum-eroeffnet,UOXB90O

Close to the university hospital and therefore close to the patient: The new Max Planck Center in Erlangen is intended to facilitate the exchange between basic research and medicine. The new building has now been opened, where research into long Covid is also being carried out.

...

The blood samples collected since 2021 are currently being analyzed. However, there are no initial results yet. "If everything goes well, we will know in six months whether we have a chance of seeing differences between long-Covid patients and healthy subjects."

Translated said:Because when a doctor examines a patient for Long-Covid, it is based on questionnaires so far. "In case of doubt, it is the patient's self-report," says Guck. Based on this, it is decided whether someone has Long-Covid or not. "But there is no objective marker that can be used to check what is really going on in the patient's body." That's why Long-Covid is so stigmatized. "Because then the assumptions are very obvious that it is psychosomatic, that one only imagines that."

Professor Guck and his research team are sure that there must be a measurable cause for long Covid that has not yet been found. In search of this proof, the scientists have now collected more than 1,000 blood samples. The key question is: What shape do the cells have? And: Do the cells in the blood of a long Covid patient have a different form than that of a healthy person?

The MPZPM is a joint research center of the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Light, the FAU Erlangen-Nuremberg and the University Hospital Erlangen.

This is Martin Kräter's work, initially at the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Light. One of our comments from 2022 —

Martin's technology looks really interesting. It will be good to see measurements of deformability of red blood cells specifically for Long Covid cohorts clearly from 6 months or a year after infection and compared with cells from post-Covid healthy people.

Prior to publication, some of this data has been presented at the UniteToFight conference in May 2024.

Andy

Senior Member (Voting rights)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für ME/CFS have published an open letter. Below is an automatic translation of their Facebook post describing it.

"Open letter to cashier medical associations demands adequate care for ME/CFS patients in accordance with the G-BA's long-COVID policy

The in-patient organizations Initiative LiegendDemo and DG ME/CFS, supported by Lost Voices Stiftung and ME Hilfe initiate an open letter to the cash register associations.

Organizations see some hurdles in implementing the G-BA’s Long COV-RL as the current care structures for the care of ME/CFS patients do not meet the necessary requirements.

Therefore, the organizations are asking the registrar associations:

- To educate the general and specialist doctors in relation to all patient groups.

- To offer field-wide training designed by ME/CFS experts.

- To ensure that severely restricted ME/CFS patients* or complex illnesses receive the intended home visits or telemedical services.

- To advocate for specialized outpatient contact points for all patients with ME/CFS.

- Negotiate with the health insurance for adequate compensation.

- To ensure that all ME/CFS affected, regardless of the cause of their disease, are taken into account within the framework of the "Long COVID off-label-use" list of medicines commissioned by the BMG.

Go to the open letter here: www.mecfs.de/kv-brief"

Original text in German

Facebook post, https://www.facebook.com/dg.mecfs/p...B4V5QhQVnYroRLSWJs4QxCiMUFaFfJenedvxwXuvRQbAl

"Open letter to cashier medical associations demands adequate care for ME/CFS patients in accordance with the G-BA's long-COVID policy

The in-patient organizations Initiative LiegendDemo and DG ME/CFS, supported by Lost Voices Stiftung and ME Hilfe initiate an open letter to the cash register associations.

Organizations see some hurdles in implementing the G-BA’s Long COV-RL as the current care structures for the care of ME/CFS patients do not meet the necessary requirements.

Therefore, the organizations are asking the registrar associations:

- To educate the general and specialist doctors in relation to all patient groups.

- To offer field-wide training designed by ME/CFS experts.

- To ensure that severely restricted ME/CFS patients* or complex illnesses receive the intended home visits or telemedical services.

- To advocate for specialized outpatient contact points for all patients with ME/CFS.

- Negotiate with the health insurance for adequate compensation.

- To ensure that all ME/CFS affected, regardless of the cause of their disease, are taken into account within the framework of the "Long COVID off-label-use" list of medicines commissioned by the BMG.

Go to the open letter here: www.mecfs.de/kv-brief"

Original text in German

Offener Brief an Kassenärztliche Vereinigungen fordert angemessene Versorgung ME/CFS-Erkrankter gemäß der Long-COVID-Richtlinie des G-BA

Die Patient*innenorganisationen Initiative LiegendDemo und DG ME/CFS, unterstützt durch die Lost Voices Stiftung und ME Hilfe, initiieren einen offenen Brief an die Kassenärztlichen Vereinigungen.

Für die Umsetzung der Long COV-RL des G-BA sehen die Organisationen einige Hürden, da die aktuellen Versorgungsstrukturen für die Versorgung von ME/CFS-Erkrankten nicht die nötigen Voraussetzungen erfüllen.

Daher bitten die Organisationen die Kassenärztlichen Vereinigungen:

- Die Haus- und Fachärzt*innen in Bezug auf alle Patientengruppen aufzuklären.

- Flächendeckend Fortbildungen anzubieten, die von ME/CFS-Expert*innen konzipiert werden.

- Dafür zu sorgen, dass schwerer eingeschränkte ME/CFS-Patient*innen oder komplexer Erkrankte die vorgesehenen Hausbesuche oder telemedizinischen Versorgungsangebote erhalten.

- Sich für spezialisierte ambulante Anlaufstellen für alle ME/CFS-Erkrankten einzusetzen.

- Sich in Verhandlungen mit den Krankenkassen für adäquate Vergütung einzusetzen.

- Sich dafür einzusetzen, dass alle ME/CFS-Betroffenen, unabhängig vom Auslöser ihrer Erkrankung, im Rahmen der vom BMG in Auftrag gegebenen "Long COVID off-label-use"-Medikamentenliste berücksichtigt werden.

Hier geht es zum offenen Brief: www.mecfs.de/kv-brief

Facebook post, https://www.facebook.com/dg.mecfs/p...B4V5QhQVnYroRLSWJs4QxCiMUFaFfJenedvxwXuvRQbAl

NelliePledge

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Kassenarztliche vereiningung = health insurers

rvallee

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Christian Zacharias, a German pwME, has published a book titled "Everything is psychosomatic".

Because, somehow, this is one of the most controversial things out there, he couldn't find a publisher willing to market it. Shows how insane the situation is, that this issue is systematically ignored by editors and publishers, who often publish works on issues that are technically much more controversial, but this is a whole-of-society controversy, and that makes it taboo, unlike events contained in a small community or elsewhere around the world.

After two and a half years, the time has finally come: My book "Everything psychosomatic!" is finished! In it, I tell how, despite the fairly clear facts, numerous doctors let me go to pieces and repeatedly gave me psychosomatic diagnoses.

I write about #MECFS and #LongCovid, the plight of those affected, their fight for research and education, the sabotage of this fight by some doctors and the sluggish reaction of politicians

Because, somehow, this is one of the most controversial things out there, he couldn't find a publisher willing to market it. Shows how insane the situation is, that this issue is systematically ignored by editors and publishers, who often publish works on issues that are technically much more controversial, but this is a whole-of-society controversy, and that makes it taboo, unlike events contained in a small community or elsewhere around the world.

rvallee

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

"Lying down" demonstration in front of the German Ministry of Research today:

Edit: another photo, good turnout.

#Lyingdemo in front of the Ministry of Research: Those affected and their families demand research, care & recognition of #MECFS & #PostCovid . Don't leave them alone!

Edit: another photo, good turnout.

Last edited:

article is from April 2024

https://www.riffreporter.de/de/wiss...ldiagnosen-long-covid-fatigue-immunadsorption

ME/CFS: Leading neurologist criticizes numerous misdiagnoses of multisystem disease

https://www.riffreporter.de/de/wiss...ldiagnosen-long-covid-fatigue-immunadsorption

ME/CFS: Leading neurologist criticizes numerous misdiagnoses of multisystem disease

Google translate:

ME/CFS has been officially recognized as a neurological disease for more than 50 years and is considered the most severe form of long Covid - but it remains highly controversial in neurology to this day. In an interview, Charité Professor H. Prüß

explains where his professional association stands and when those affected can hope for therapies

The World Health Organization has listed ME/CFS as a neurological disease since 1969. Nevertheless, the chronic multisystem disease, which often occurs post-virally, is not recognized by all neurologists. The corona pandemic and its long-term consequences have not been able to change this, although ME/CFS is considered a particularly severe form of long Covid. The nature of the syndrome is a matter of difference between psychosomatic and organic disease, the correct diagnosis and therapy - and the question of how many people are actually affected.

What is the position of the German Society of Neurology (DGN) on these questions? RiffReporter spoke to H. Prüß, the spokesperson for the DGN Neuroimmunology Commission. The Charité professor also provides information on the status of his study on a possible therapy method for long Covid and ME/CFS sufferers, immunoadsorption - and promises a new medical guideline.

Mr Prüß, the multisystem disease ME/CFS is highly controversial in neurology: some consider it to be underdiagnosed, others question it fundamentally. Who is right?

In my personal opinion, this disease undoubtedly exists. For example, we know clear risk factors - women with previous mental illnesses, for example, are more likely to develop ME/CFS. There is much to suggest that we are dealing with a disease with its own mechanisms that we just don't yet fully understand.

So why the argument?

Before doctors are convinced of a diagnosis, they always look for a single disease mechanism in their patients for good reason. But we don't have one with ME/CFS. The disease has had a name for 50 years, but we still don't have a biomarker to prove it. The symptoms are so diverse and overlap strongly with other diseases, including many psychological ones. According to an outdated view, some doctors also assume that psychological symptoms are not an organic disease. I see it completely differently, but all of this makes it so difficult. Last but not least, a major problem is that the diagnoses are often made by the patients themselves. This is understandable, because it is of course more pleasant when symptoms are attributed to an external event such as a viral disease. But self-diagnoses dilute the clinical picture considerably. For every person with real ME/CFS, there are probably several who only attribute this diagnosis to themselves.

How many people do you think are actually affected - and how many ME/CFS patients have been added as a result of long Covid?

There is no good survey on this. The figure of 300,000 people is often mentioned. I suspect that only perhaps 20 percent of these, or 60,000 people, actually have ME/CFS. In my view, there is no serious evidence that this number has increased dramatically as a result of the pandemic.

The main symptom of ME/CFS is usually post-exertional malaise (PEM), a deterioration in condition after exertion. Do you agree?

PEM is the main symptom, and patients should be tested for it. If slight exertion leads to disproportionate weakness, this diagnosis is also plausible.

What makes the focus on PEM in neurology so controversial?

Colleagues also see patients who are suspected of having ME/CFS and who come to the clinic for evaluation and report that they can no longer get out of bed. However, during the rounds they never find them in their room because they are downstairs smoking – and if the elevator doesn’t come fast enough, they take the stairs. This is where self-perception and external perception don’t match up. One problem is when doctors generalise such experiences. This does not do justice to the really seriously ill patients who spend most of the day in bed. In addition, fatigue – one of the most common symptoms of ME/CFS – is also widespread in the healthy normal population. It affects up to ten percent of people, and at a level of severity similar to ME/CFS. It is therefore not always easy to recognise what is special about it compared to other illnesses

Some neurologists generally classify ME/CFS patients as psychosomatic and suspect that they are more likely to have depression. What is the DGN's view on this?

The DGN is divided on this. Psychological comorbidities are common, but I see organic involvement in some patients. In another part, perhaps the larger part, the psychosomatic is actually in the foreground - and that does not mean that these people do not suffer. We know this from children who develop stomach aches because they are afraid of school. These complaints are real, and yet they can of course disappear. That is why we should also examine ME/CFS patients psychosomatically without exception, because if they are mentally ill, we can already help them well. However, we prevent this approach if we work with blood dialysis or oxygen therapy instead.

Will this be the first time there will be an independent ME/CFS guideline?

It will probably be a fatigue guideline with special consideration of ME/CFS - that is part of the compromise. To be honest, we hardly have any concrete recommendations for ME/CFS. Of course it will be about "pacing" [a form of energy management recommended for ME/CFS patients; editor's note], but that essentially just means that a patient does not overexert themselves if it is not good for them. That is actually common sense. The most important thing is that all patients are given an interdisciplinary organic and psychological assessment.

Critical voices criticize the state funding of long Covid and ME/CFS research, and believe that public money would be better invested elsewhere. What do you think of that?

There is broad agreement within the DGN that more research is necessary. The fact that there are other voices calling for this is linked to this diffuse mood: there are numerous patients, you can't really help them, there isn't enough time for a comprehensive organic and psychological assessment. At the same time, there are many mentally ill people who are not cared for because they can't find a psychotherapist. All of this is unsatisfactory and some contributions are perhaps also an expression of helplessness.

You are involved in clinical studies on immunoadsorption, a blood washing procedure that filters autoantibodies from the blood and could help long-Covid and ME/CFS patients. What can you tell us about the results so far?

So far, I can only say that we are making technical progress. The study is extremely complex, double-blind and with a sham treatment in the control group. It will take us until the end of 2024 to include all patients. Then we will start evaluating the results as quickly as possible.

The attention given to long Covid has recently enabled a number of clinical trials that should also benefit ME/CFS sufferers. Can you give them hope that there will be a curative therapy in the near future?

Unfortunately, there is definitely no curative therapy - there is no such thing for almost any chronic disease. However, there should be treatments within the next five years that will help some patients a lot. I also expect that we will make progress through better interdisciplinary assessment. We will have a better understanding of what triggers ME/CFS, and studies are underway, for example, for a vaccine against the Epstein-Barr virus that may be able to prevent ME/CFS in the future. I also hope that in the future it will no longer be a red flag when we tell a patient that psychological factors play a role. Then more sufferers will benefit from psychiatric or psychotherapeutic intervention, whether pharmacological or with talk therapy. So far, this is not even offered to most ME/CFS patients, although there is still evidence for the slightly positive effects of behavioral therapy

Patients complain about a poor care situation: They can hardly find any doctors who are familiar with ME/CFS - and because nothing can be proven with standard diagnostics, they often receive an incorrect psychological diagnosis. Some doctors also warn against such misdiagnoses. Does the DGN agree?

There is no majority opinion of the DGN so far. Most would probably agree that there is a risk of misdiagnosis - in both directions. We have patients with ME/CFS who are diagnosed with depression. They are then sent to an activating rehabilitation program in the assumption that warm baths and physiotherapy will get them better - and then they completely collapse. However, I suspect that even more people with an adjustment disorder, personality disorder or another mental illness are misdiagnosed with ME/CFS. If you tell them not to overexert themselves and do not offer psychotherapy, you are doing them just as much harm. That is the big problem: At the moment we are not really helping those who are suffering severely from ME/CFS - or those who wrongly believe that they have ME/CFS.

On behalf of the federal government, the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) analyzed the knowledge on ME/CFS. It came to the conclusion that there is no evidence of the benefit of activating therapies, as they are often used in rehabilitation - but that a deterioration in the condition cannot be ruled out. Some therapists therefore demand: no rehabilitation if PEM is diagnosed. Do you agree?

If PEM can be objectified through behavioral observation and is not based exclusively on self-perception, I agree. Of course, the vivid individual cases of people who come out of rehabilitation in a wheelchair are anything but representative. But if PEM is clearly diagnosed, people cannot be forced into rehabilitation that relies on physical activation. Otherwise they will suffer a setback.

Federal Health Minister Karl Lauterbach wants to make it easier for people with long-term Covid to access therapies that have so far only been sufficiently researched and approved for other diseases. Should there also be such an off-label list for people who have ME/CFS independently of corona?

That is a good idea - but it would be a Herculean task to compile the list. We just don't have the evidence yet. Of course, there are not only quacks who want to make money with expensive therapy offers, but also doctors who are convinced of experimental therapies for ME/CFS and report good experiences. But if their patients experience improvements, it is not possible to check whether these have occurred spontaneously or are due to therapy. What appears to help individuals cannot therefore be generalized without accepting that it may harm others. I fear that patients and doctors have to endure this dilemma. At the moment they can only try something out in specific constellations in individual cases. If you search the internet, you will find an endless number of tips for ME/CFS: cold showers - warm showers, eating this - definitely not that, dialysis, cortisone and much, much more. If there are so many different tips, unfortunately there is some evidence to suggest that none of them work in the long term.

Last edited:

Gosh, that was a roller coaster. Good, bad, ugly, confused...ME/CFS: Leading neurologist criticizes numerous misdiagnoses of multisystem disease

we know clear risk factors - women with previous mental illnesses, for example, are more likely to develop ME/CFS.

In addition, fatigue – one of the most common symptoms of ME/CFS – is also widespread in the healthy normal population. It affects up to ten percent of people, and at a level of severity similar to ME/CFS. It is therefore not always easy to recognise what is special about it compared to other illnesses

This Professor H. Prüß, what role does he have in the fatigue guideline he talks about, and how influential will it be?Psychological comorbidities are common, but I see organic involvement in some patients. In another part, perhaps the larger part, the psychosomatic is actually in the foreground - and that does not mean that these people do not suffer. We know this from children who develop stomach aches because they are afraid of school. These complaints are real, and yet they can of course disappear. That is why we should also examine ME/CFS patients psychosomatically without exception, because if they are mentally ill, we can already help them well. However, we prevent this approach if we work with blood dialysis or oxygen therapy instead.

Jonathan Edwards

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Gosh, that was a roller coaster. Good, bad, ugly, confused...

A weird mixture of reasonably sensible statements and misleading ones.

Interesting that they seem to be doing a decent (hopefully) trial of immunoadsorption.

I wouldn't be able to justify offering it to patients but if it gives us a result it will be useful to others at least.

We haven't had much comment from British neurologists on what they think. Maybe in Germany neurologists like to haveME/CFS under them to boost their clientele whereas in the UK private neurology is a pretty limited game.

This Professor H. Prüß, what role does he have in the fatigue guideline he talks about, and how influential will it be?

"Prof. Dr. H. Prüß is the director of the Department of Experimental Neurology at the Berlin Charité, a neuroscientist at the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) in Berlin, and spokesperson for the Neuroimmunology Commission of the German Society of Neurology (DGN). His research focuses on the mechanisms by which autoantibodies trigger neuropsychiatric diseases. He is currently supporting the DGN in putting together a team of authors who will develop the first guideline on fatigue (chronic exhaustion) and ME/CFS." Google Translate

rvallee

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Whew, that is one confused individual who is adding as much clarity to the issue as throwing mud helps make water crystal clear. Basically rehashing all the tropes while lamenting wistfully about how, sometimes, maybe there is something but, who knows?article is from April 2024

https://www.riffreporter.de/de/wiss...ldiagnosen-long-covid-fatigue-immunadsorption

ME/CFS: Leading neurologist criticizes numerous misdiagnoses of multisystem disease

For sure he really wants to make sure that people think it's psychological and that psychology is important and that it should be foremost considered psychosomatic and that there is a lot of confusion about how it's sometimes misinterpreted as psychological, but is likely so in most cases and also have people considered that it's psychological and behavioral and possibly psychobehavioral?

Reminds of me young earth creationists, who may have the odd fact correct but only to make an argument about how, you know, the earth is just very young and evidence is conflicted and so on.

It would definitely be preferable if this person was not involved in anything having to do with us. Or say anything about the issue ever again. Now that is crystal clear. No wonder we never see any progress. These people have no clue what they're talking about but want to get involved somehow.

We have split off a discussion to a new thread in the Possible Causes and Predisposing Factor discussion subforum:

Pre-existing mental illness as a risk factor for ME/CFS

Pre-existing mental illness as a risk factor for ME/CFS

rvallee

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Some videos, probably only viewable on Xitter:"Lying down" demonstration in front of the German Ministry of Research today:

Edit: another photo, good turnout.

In her moving speech, @BerlinBuyers founder Sophie shared the story of her former colleague Taylor with us. A story full of strength, but also a story of mistreatment and hopelessness. A story that so many of us know!

rvallee

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

The German government has approved a €15M research program, funding 7 projects and a research network. Looks not so bad, although rather small, but all biomedical.

https://www.gesundheitsforschung-bmbf.de/de/pathomechanismen-von-me-cfs-18010.php

Thread with a summary of the projects:

https://www.gesundheitsforschung-bmbf.de/de/pathomechanismen-von-me-cfs-18010.php

Thread with a summary of the projects:

More X posts from @ME/CFS Skeptic:

2. There is one individual project called FAME which receives € 1.75. It is led by Dr. Bettina Hohberger and will study the role of autoantibodies against G protein-coupled receptors in ME/CFS patients.

3. The BioSig-PEM research network will look for biopathological signatures of post-exertional malaise in ME/CFS. it consists of multiple parts and includes studies on Raman spectroscopy and tryptophan metabolism.

4. The CURE-ME project aims to investigate (auto-)immune processes in ME/CFS including analysis of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) auto-antigens.

5. The MIRACLE research network will investigate immunological, inflammatory and metabolic signaling pathways in ME/CFS. In particular, it will take a closer look at the HDL proteome and the role of granulocytes in ME/CFS patients.

6. The SERIMM project focuses an altered metabolism of the neurotransmitter serotonin and a dysregulation of the immune system. It also includes a SARS-CoV-2-induced mouse model of ME/CFS.

7. SLEEP-NEURO-PATH will study sleep characteristics with a focus on brain function and blood flow. It includes mobile sleep examinations in adolescent patients.

8. Lastly, VADYS-ME focuses on vascular dysfunction and reduced blood perfusion in patients with ME/CFS. A sub-study of the research cluster will look at retinal vascular analysis as a potential diagnostic marker in post-infectious ME/CFS.

2. There is one individual project called FAME which receives € 1.75. It is led by Dr. Bettina Hohberger and will study the role of autoantibodies against G protein-coupled receptors in ME/CFS patients.

3. The BioSig-PEM research network will look for biopathological signatures of post-exertional malaise in ME/CFS. it consists of multiple parts and includes studies on Raman spectroscopy and tryptophan metabolism.

4. The CURE-ME project aims to investigate (auto-)immune processes in ME/CFS including analysis of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) auto-antigens.

5. The MIRACLE research network will investigate immunological, inflammatory and metabolic signaling pathways in ME/CFS. In particular, it will take a closer look at the HDL proteome and the role of granulocytes in ME/CFS patients.

6. The SERIMM project focuses an altered metabolism of the neurotransmitter serotonin and a dysregulation of the immune system. It also includes a SARS-CoV-2-induced mouse model of ME/CFS.

7. SLEEP-NEURO-PATH will study sleep characteristics with a focus on brain function and blood flow. It includes mobile sleep examinations in adolescent patients.

8. Lastly, VADYS-ME focuses on vascular dysfunction and reduced blood perfusion in patients with ME/CFS. A sub-study of the research cluster will look at retinal vascular analysis as a potential diagnostic marker in post-infectious ME/CFS.