cassava7

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Hormones and chromosomes

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01836-9

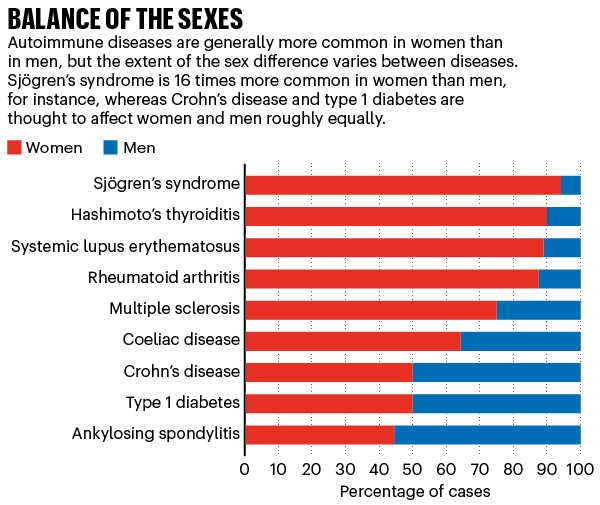

Around the world, an estimated 4% of people have at least one autoimmune disease. In the United States, the figure is about twice that. The prevalence of these diseases is different in men and women (see ‘Balance of the sexes’). There are also sex differences in when symptoms manifest and how severe they are.

Some of the earliest theories to explain these discrepancies focused on sex hormones, which regulate the innate and adaptive immune systems through multiple pathways, by means of receptors on immune cells.

Hormones could help to explain why some people with autoimmune disease see their symptoms improve or worsen when hormone levels surge or drop, such as during puberty, pregnancy and menopause, [Rhonda] Voskuhl [a neuroimmunologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, and president of the interdisciplinary Organization for the Study of Sex Differences] says. For example, throughout the second half of pregnancy when oestrogen hormones surge, women with MS experience a 70% reduction in relapses3. As oestrogen levels drop after delivery, however, symptoms tend to return — and women with lupus don’t get the reprieve at all.

It is unclear whether female predominance in many autoimmune diseases is a result of higher levels of female hormones such as oestrogen, low levels of male hormones such as testosterone, or a combination of the two, says Susan Kovats, an immunologist at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation in Oklahoma City. Scientists are also still working out the various effects that these hormones have on the immune system — both positive and negative.

But the hormone theory has competition. Some researchers suggest that sex chromosomes might be the culprit. In animal studies, mice with two X chromosomes develop conditions such as lupus more frequently than do XY mice, even when all the mice are engineered to have the same sex organs and hormones. Likewise, men with Klinefelter syndrome, who have an extra X chromosome, develop lupus and Sjögren’s syndrome at rates similar to those in women4.

A potential explanation for this could lie in the numerous genes on X chromosomes that have been found to be involved in immune function. Where more than one X chromosome is present in a cell, as is typical in women, all but one copy is usually deactivated. However, it is thought that as many as 23% of X-linked genes escape deactivation5 — including those that affect immune function. Having multiple copies of those genes that remain active can lead to an over-active immune response and the development of disease. The incomplete inactivation of the X-linked gene TLR7, for instance, has now been implicated in increasing the risk of developing lupus.

[Note: since the publication of this article, a TLR7 gain-of-function genetic variation has been found to cause human lupus.]

The newest theories for what causes sex differences in autoimmune diseases points to a complex set of interactions between hormones, X chromosomes and other physiological factors, Voskuhl says. Shifting hormone levels throughout life, for example, might mask or unmask the influence of X chromosomes. The organ targeted by a specific disease also alters each condition’s trajectory.

“Historically, there’s been sort of the hormone camp, and then there’s been the X-chromosome camp,” Kovats says. But the latest research, she argues, undermines this neat sorting. “With this finding of immune response genes on the X chromosome and the fact that oestrogen receptors seem to regulate some of the same things, it brings a little bit of a convergence.”

Digging into the nuances of immune responses across sexes could lead directly to new treatments for all sorts of disease, Voskuhl adds. “If there’s not any difference, that’s a win because what you’ve just discovered is relevant to 100% of the population,” she says. “On the other hand, if you find that there is a sex difference, now you can figure that out. It’s good for males and females.”

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01836-9The pregnancy challenge

As evidence has accumulated to illuminate how hormones, sex chromosomes and other factors contribute to an elevated risk of disease in women, some researchers have taken a big-picture view to investigate the evolutionary pressures that might have led to sex discrepancies in autoimmune diseases. One leading theory focuses on a unique challenge that women face: how to grow a genetically distinct human in their bodies without their immune systems rejecting the fetus as a foreign object.

The female immune system has developed a complicated strategy that enables it to fight off pathogens without endangering the fetus, says Melissa Wilson, a geneticist and evolutionary biologist at Arizona State University in Tempe. At various stages of pregnancy, she says, the body seems to ramp up and turn down the immune response. As the body prepares for pregnancy, for example, inflammation increases to allow implantation of a fertilized egg. This inflammatory response resembles how the body reacts to an open wound and could help to explain why many women feel unwell in the first trimester, according to some research6. During that period, the embryo needs to break through the lining of the uterus, damage the tissues there, take over some of the mother’s blood vessels, and establish blood supply to the fetus through the placenta. Inflammation aids this process of damage and repair, along with the removal of waste products.

Inflammation drops during the second trimester and then increases again in the third, especially as birth becomes imminent. The placenta itself produces the oestrogen hormone oestriol, which has such powerful anti-inflammatory effects that clinical trials are under way to assess its ability to treat women with MS. Many questions remain about how pregnancy affects the immune system, and the interaction with the placenta in particular, Wilson adds. “We try to tell a simple story, but the truth is it’s not simple and we don’t understand it well,” she says. “The more we understand, the more we realize how mind-boggling it all is.”

The evolution of the placenta might have driven some of the sex differences in autoimmune disease that are now being uncovered, Wilson and her colleagues proposed in a 2019 paper2. However, the female system evolved over hundreds of millennia during which people were pregnant for much of their reproductive years. Because people have fewer children now than their ancestors typically did, their bodies do not interact with a placenta as frequently. Without regular placental influence to keep the female immune system in check, the researchers suggest, autoimmune attack might be more likely. In urban, industrialized populations, women exhibit a higher prevalence of autoimmune disease than do men, and those trends might reflect hormonal shifts as a result of urbanization and a move towards more-sedentary lifestyles, Wilson’s team proposes. Autoimmune diseases have increased in incidence in recent decades, and rates are highest where increased use of contraception has reduced the number of pregnancies. Sedentary lifestyles also affect reproductive hormone levels2.

Unanswered questions remain, including whether women who have fewer or no children have an elevated risk of autoimmune disease. Wilson is also planning to investigate whether the age a person is when they have their first baby affects the likelihood of disease. It’s possible, she says, that getting pregnant earlier in life might be protective. Working out the details could lead to new treatments — if researchers were to find that oestriol is really important, for instance, then Wilson speculates that the hormone could be used as a preventive therapy for young people. “That time window might be important for reducing risk of autoimmune disease,” she says.

Theories such as these make sense, Voskuhl says. From an evolutionary perspective, it would have been beneficial for mothers to be able to stay healthy while also carrying pregnancies to term. “The women need to survive to take care of the babies,” Voskuhl says. “The babies that had mothers who had active immune systems — they lived and perpetuated that particular pattern.”

Last edited: