Arvo

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

While researching the origins of the ideas regarding ME, I came across this paper. I'm going to post it in full, translated, because I think it's also a document of key importance for UK researchers interested in the history of the Wessely School's ideas about ME.

It appeared in Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde (Dutch Journal of Medicine) in October 1991 (accepted July 26th 1991); Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde 1991; 135, nr 43, page 2014-2017, which included several other articles about CFS, including the first official publications of the Dutch Nijmegen group.

Translated with Google translate and then refined by me:

The chronic fatigue syndrome; psychiatric aspects, 1991, K.E. Hawton and M.W. Hengeveld.

28-10-1991

See also the articles on p. 2005, 2010, 2017 and 2019 .

A number of contributions in this journal issue are devoted to chronic fatigue syndrome. This article provides an overview of the characteristics and possible psychiatric and psychosocial causes of this syndrome. In addition, a cognitive-behavioral therapeutic approach as developed in the United Kingdom is described.

CHARACTERISTICS

Chronic fatigue syndrome is likely synonymous with or related to several other syndromes, which have been given a rich variety of names, such as epidemic (or post-infectious) neuromyasthenia, neurocirculatory asthenia, myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), post-viral fatigue syndrome, and chronic Epstein-Barr syndrome. . However, the frequently used term chronic fatigue syndrome is preferable because it implies no suspicion of its cause.

Recently, at a consensus meeting of UK experts, diagnostic criteria have been developed for future research into chronic fatigue. 1Two syndromes were described: the chronic tiredness syndrome (CMS; [het chronische-moeheidssyndroom] ‘chronic fatigue syndrome’) and the post-infectious tirednes ssyndrome (PIMS; [het postinfectieuze moeheidssyndroom] ‘post-infectious fatigue syndrome’), a subtype of the CMS. The criteria for the CMS are: a syndrome characterized by severe and debilitating tiredness as the main complaint, impairing both physical and psychological functioning, with a clear onset (ie not for life) and present for at least six months for more than 50% of the time. Side complaints may also be present, such as persistent sore throat, headache, muscle aches, sensations of fever, and swollen joints and lymph nodes. Common psychological complaints are: sadness, crying spells, irritability, concentration problems, insomnia or excessive need for sleep,feelings of hopelessness and even suicidal thoughts. Exclusion criteria are: physical illnesses known to cause severe tiredness (eg severe anemia) and schizophrenia, manic-depressive disorders, psychotropic substance abuse, eating disorders or organic-psychiatric disorders. Other psychiatric disorders (including non-bipolar major depressive disorders, anxiety disorders and hyperventilation syndrome) are not necessarily grounds for exclusion, especially because they could also occur secondary to the CMS.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE TIREDNESS

There is a pronounced muscle fatigue at the CMS. Patients usually complain that exercising is extremely demanding and leads to severe fatigue that can last for hours, days, or even weeks. The fatigue seems to be of a central nature: muscle function is generally normal and the muscles are neither weakened nor noticeably fatigued. 2 3 Nor have there been any indications of impaired neuropsychological functioning in objective tests, while psychological fatigue is also an important complaint at the CMS. 4

PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

A high prevalence of psychiatric disorders has been found in patients with the CMS. 5-10 For example, of 100 patients with CMS presented to an internal medicine outpatient clinic in the US, 66 were found to have one or more psychiatric disorders: 47 had depressive disorders, 15 somatization disorders and 9 anxiety disorders. 7 Depressive disorders are the most common psychiatric diagnosis in all studies, ranging from nearly half to more than two-thirds of cases. It is important, however, that depressive disorders have never been diagnosed in àll cases.

CAUSES

Psychiatric causes.

While it is well established that psychiatric disorders, especially depression, play an important role in patients with CMS, the nature of this role is unclear. One study found a greater number of depressive episodes in the history of patients with CMS than would be expected, 5 while another study found no difference with the general population in this regard. 10There may be an association between susceptibility to major depressive disorder and susceptibility to the CMS. It is likely that the depression is part of the syndrome rather than a response to it, as major depressive disorder was more frequently diagnosed in patients with CMS than in patients with at least equally disabling neuromuscular diseases. 9 Another possibility is that the CMS is a variant of major depressive disorder. An essential difference is that depressed patients with CMS, compared to a control group of depressed psychiatric patients, were much more likely to attribute their illness to a physical cause. 9 In addition, a large minority of patients with CMS do not meet the criteria for a major depressive or other psychiatric disorder.

Psychosocial causes.

Several authors have pointed to the striking susceptibility to CMS of people who had consistently worked very actively on their physical fitness. Excessive exercise could lead to an increased risk of CMS, but such people may also be overprotective of physical symptoms and therefore respond more strongly to post-infectious fatigue.

Like neurasthenia towards the end of the last century, 11 CMS is a fashion diagnosis. The general, positive interest in the syndrome probably shapes the complaints of people who have various disorders, both psychiatric and somatic, by which an epidemic of the syndrome suddenly seems to appear. Other suggested causes of the CMS are the speed and pressure of modern existence, like it was said about the neurasthenia a century ago. 12 Although such general ideas probably contribute little to our understanding of the syndrome, the specific role of stress in the CMS needs further investigation.

The firm belief of many patients with CMS that their disease is caused by a viral infection may also be of significance for the maintenance of complaints, as evidenced by a follow-up study that found a link between this belief and an unfavorable course . 13 Another factor that contributes to the maintenance of the CMS may be the belief, reinforced by patient associations and by some authors, 14 that physical and mental exertion lead to damage and possible relapse, so patients should rest as much as possible. Some patients with the CMS spend months or even years in relative inactivity.

With the current state of our knowledge, it seems sensible to take an open stance about the causes, avoiding an artificial mind-body dualism. 15 The most suitable is an interactive causal model, in which somatic, psychiatric and psychosocial factors can be integrated. It is also very important to distinguish between predisposing factors, luxerende* factors and factors that maintain the CMS.

DIAGNOSTICS

In patients who present with chronic fatigue, the physician should of course take a complete history, including somatic, psychiatric and psychosocial, perform a thorough physical examination and have laboratory tests performed, necessary to rule out a physical illness. Some authors recommend a very large number of laboratory tests as routine, 16 but most now consider this wasteful given the small number of positive outcomes. 17 Extensive research can even be harmful, as it could reinforce the patient's belief that there is a physical illness. Requesting an examination is often interpreted as an expression of uncertainty on the part of the doctor.

TREATMENT

Psychiatric treatment.

Many patients with CMS are reluctant to be referred to a psychiatrist or psychologist, partly because of their conviction that they have a physical illness, and partly because they believe this suggests that they are not being taken seriously. Any referral must therefore be made carefully and with great explanation; good cooperation between the referring physician and the psychiatrist or psychologist is decisive for the patient's acceptance of the referral.

Antidepressants.

Although no control group studies have been conducted on the effects of antidepressants in the CMS, their use is supported by the high prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in the CMS and the demonstrated efficacy of a low dose of a tricyclic antidepressant in fibromyalgia. 18 One objection to its use is the low tolerance of patients with CMS to the side effects of antidepressants. In patients with a clear depressive disorder, a trial treatment is certainly recommended, in combination with sufficient guidance and support.

Cognitive behavioral therapy.

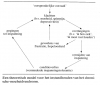

Whatever the predisposing and luxerende* causes, the CMS is in many cases maintained by specific ideas about the disease (such as: 'I have a chronic physical illness', 'Exertion is harmful to me' and 'I must rest' ) and the resulting behavior (such as: avoiding effort and social contacts). As a result of a loss of condition, every effort leads to physical complaints, which in turn confirms the ideas described. 19 Thus the patient gets into a vicious circle (figure), resulting in feelings of frustration, depression and hopelessness, which in turn contribute to the feeling of illness. This theoretical model has three advantages: it is free from assumptions about the original causes of the syndrome, it is acceptable to many (but not all) patients, and it can form the basis of cognitive-behavioral therapeutical treatment.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is a form of psychotherapy that was originally developed for depressed patients, but has since been shown to be useful for many other psychiatric disorders. 20 The aim of this therapy is to change disturbing behaviors and thoughts, which may underlie the continued existence of psychological disorders and problems. In patients with CMS, the aim is first of all to explain the described model, then to revise the ideas mentioned about the disease and finally to gradually implement a somatic and psychological rehabilitation program that restores the original way of life as much as possible. .

While other psychological approaches to the CMS are conceivable, the cognitive-behavioral therapy certainly seems promising. An English open study of this treatment in 55 severely disabled patients with CMS resulted in statistically significant and lasting improvements in functioning in 69% of the 32 patients who were willing to have the treatment. 21 For a number of these patients it was a matter of a full recovery of the previous level of functioning. Control group studies into this form of therapy are now being conducted.

CONCLUSION

The chronic tiredness syndrome leads to severe morbidity and has a poor prognosis. Although a considerable amount of research has been done, a convincing somatic explanation for the syndrome is lacking to date. A lot of patients with CMS have a psychiatric disorder, especially a depressive syndrome.

Despite the feelings of powerlessness that patients with CMS evoke in their doctors, their complaints deserve serious attention and every effort should be made to help them. In our view, extensive somatic aid inverstigation is not useful and may be harmful. Antidepressants should be considered when marked major depressive disorder exists. Careful examination of the factors that may maintain the syndrome should precede advice for gradual rehabilitation, requiring comprehensive support and understanding of patients. This approach can certainly be applied by the general practitioner.Referral to a specialist is necessary if the GP does not have sufficient skills or patience or if the patient shows severe psychiatric symptoms or has very persistent ideas about the disease.

Research into the somatic and psychiatric aspects of the CMS should be continued. It is most likely to have meaningful results when it is performed in collaboration between somatic and psychiatric or psychological researchers.

This article was written during the period when Dr. Hawton was working as a Boerhaave Professor of Consultative Psychiatry at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Leiden.

Accepted on July 26th 1991

*Note of translator: The original tekst speaks of “luxerende factoren”, which can be said to correspond with ‘precipitating factors’. However, in dutch “luxerend” explicitly specifies events that provoke a psychiatric disorder, and I didn’t want to translate it in a way that lost the original meaning and context.

It appeared in Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde (Dutch Journal of Medicine) in October 1991 (accepted July 26th 1991); Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde 1991; 135, nr 43, page 2014-2017, which included several other articles about CFS, including the first official publications of the Dutch Nijmegen group.

Translated with Google translate and then refined by me:

The chronic fatigue syndrome; psychiatric aspects, 1991, K.E. Hawton and M.W. Hengeveld.

28-10-1991

See also the articles on p. 2005, 2010, 2017 and 2019 .

A number of contributions in this journal issue are devoted to chronic fatigue syndrome. This article provides an overview of the characteristics and possible psychiatric and psychosocial causes of this syndrome. In addition, a cognitive-behavioral therapeutic approach as developed in the United Kingdom is described.

CHARACTERISTICS

Chronic fatigue syndrome is likely synonymous with or related to several other syndromes, which have been given a rich variety of names, such as epidemic (or post-infectious) neuromyasthenia, neurocirculatory asthenia, myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), post-viral fatigue syndrome, and chronic Epstein-Barr syndrome. . However, the frequently used term chronic fatigue syndrome is preferable because it implies no suspicion of its cause.

Recently, at a consensus meeting of UK experts, diagnostic criteria have been developed for future research into chronic fatigue. 1Two syndromes were described: the chronic tiredness syndrome (CMS; [het chronische-moeheidssyndroom] ‘chronic fatigue syndrome’) and the post-infectious tirednes ssyndrome (PIMS; [het postinfectieuze moeheidssyndroom] ‘post-infectious fatigue syndrome’), a subtype of the CMS. The criteria for the CMS are: a syndrome characterized by severe and debilitating tiredness as the main complaint, impairing both physical and psychological functioning, with a clear onset (ie not for life) and present for at least six months for more than 50% of the time. Side complaints may also be present, such as persistent sore throat, headache, muscle aches, sensations of fever, and swollen joints and lymph nodes. Common psychological complaints are: sadness, crying spells, irritability, concentration problems, insomnia or excessive need for sleep,feelings of hopelessness and even suicidal thoughts. Exclusion criteria are: physical illnesses known to cause severe tiredness (eg severe anemia) and schizophrenia, manic-depressive disorders, psychotropic substance abuse, eating disorders or organic-psychiatric disorders. Other psychiatric disorders (including non-bipolar major depressive disorders, anxiety disorders and hyperventilation syndrome) are not necessarily grounds for exclusion, especially because they could also occur secondary to the CMS.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE TIREDNESS

There is a pronounced muscle fatigue at the CMS. Patients usually complain that exercising is extremely demanding and leads to severe fatigue that can last for hours, days, or even weeks. The fatigue seems to be of a central nature: muscle function is generally normal and the muscles are neither weakened nor noticeably fatigued. 2 3 Nor have there been any indications of impaired neuropsychological functioning in objective tests, while psychological fatigue is also an important complaint at the CMS. 4

PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

A high prevalence of psychiatric disorders has been found in patients with the CMS. 5-10 For example, of 100 patients with CMS presented to an internal medicine outpatient clinic in the US, 66 were found to have one or more psychiatric disorders: 47 had depressive disorders, 15 somatization disorders and 9 anxiety disorders. 7 Depressive disorders are the most common psychiatric diagnosis in all studies, ranging from nearly half to more than two-thirds of cases. It is important, however, that depressive disorders have never been diagnosed in àll cases.

CAUSES

Psychiatric causes.

While it is well established that psychiatric disorders, especially depression, play an important role in patients with CMS, the nature of this role is unclear. One study found a greater number of depressive episodes in the history of patients with CMS than would be expected, 5 while another study found no difference with the general population in this regard. 10There may be an association between susceptibility to major depressive disorder and susceptibility to the CMS. It is likely that the depression is part of the syndrome rather than a response to it, as major depressive disorder was more frequently diagnosed in patients with CMS than in patients with at least equally disabling neuromuscular diseases. 9 Another possibility is that the CMS is a variant of major depressive disorder. An essential difference is that depressed patients with CMS, compared to a control group of depressed psychiatric patients, were much more likely to attribute their illness to a physical cause. 9 In addition, a large minority of patients with CMS do not meet the criteria for a major depressive or other psychiatric disorder.

Psychosocial causes.

Several authors have pointed to the striking susceptibility to CMS of people who had consistently worked very actively on their physical fitness. Excessive exercise could lead to an increased risk of CMS, but such people may also be overprotective of physical symptoms and therefore respond more strongly to post-infectious fatigue.

Like neurasthenia towards the end of the last century, 11 CMS is a fashion diagnosis. The general, positive interest in the syndrome probably shapes the complaints of people who have various disorders, both psychiatric and somatic, by which an epidemic of the syndrome suddenly seems to appear. Other suggested causes of the CMS are the speed and pressure of modern existence, like it was said about the neurasthenia a century ago. 12 Although such general ideas probably contribute little to our understanding of the syndrome, the specific role of stress in the CMS needs further investigation.

The firm belief of many patients with CMS that their disease is caused by a viral infection may also be of significance for the maintenance of complaints, as evidenced by a follow-up study that found a link between this belief and an unfavorable course . 13 Another factor that contributes to the maintenance of the CMS may be the belief, reinforced by patient associations and by some authors, 14 that physical and mental exertion lead to damage and possible relapse, so patients should rest as much as possible. Some patients with the CMS spend months or even years in relative inactivity.

With the current state of our knowledge, it seems sensible to take an open stance about the causes, avoiding an artificial mind-body dualism. 15 The most suitable is an interactive causal model, in which somatic, psychiatric and psychosocial factors can be integrated. It is also very important to distinguish between predisposing factors, luxerende* factors and factors that maintain the CMS.

DIAGNOSTICS

In patients who present with chronic fatigue, the physician should of course take a complete history, including somatic, psychiatric and psychosocial, perform a thorough physical examination and have laboratory tests performed, necessary to rule out a physical illness. Some authors recommend a very large number of laboratory tests as routine, 16 but most now consider this wasteful given the small number of positive outcomes. 17 Extensive research can even be harmful, as it could reinforce the patient's belief that there is a physical illness. Requesting an examination is often interpreted as an expression of uncertainty on the part of the doctor.

TREATMENT

Psychiatric treatment.

Many patients with CMS are reluctant to be referred to a psychiatrist or psychologist, partly because of their conviction that they have a physical illness, and partly because they believe this suggests that they are not being taken seriously. Any referral must therefore be made carefully and with great explanation; good cooperation between the referring physician and the psychiatrist or psychologist is decisive for the patient's acceptance of the referral.

Antidepressants.

Although no control group studies have been conducted on the effects of antidepressants in the CMS, their use is supported by the high prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in the CMS and the demonstrated efficacy of a low dose of a tricyclic antidepressant in fibromyalgia. 18 One objection to its use is the low tolerance of patients with CMS to the side effects of antidepressants. In patients with a clear depressive disorder, a trial treatment is certainly recommended, in combination with sufficient guidance and support.

Cognitive behavioral therapy.

Whatever the predisposing and luxerende* causes, the CMS is in many cases maintained by specific ideas about the disease (such as: 'I have a chronic physical illness', 'Exertion is harmful to me' and 'I must rest' ) and the resulting behavior (such as: avoiding effort and social contacts). As a result of a loss of condition, every effort leads to physical complaints, which in turn confirms the ideas described. 19 Thus the patient gets into a vicious circle (figure), resulting in feelings of frustration, depression and hopelessness, which in turn contribute to the feeling of illness. This theoretical model has three advantages: it is free from assumptions about the original causes of the syndrome, it is acceptable to many (but not all) patients, and it can form the basis of cognitive-behavioral therapeutical treatment.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is a form of psychotherapy that was originally developed for depressed patients, but has since been shown to be useful for many other psychiatric disorders. 20 The aim of this therapy is to change disturbing behaviors and thoughts, which may underlie the continued existence of psychological disorders and problems. In patients with CMS, the aim is first of all to explain the described model, then to revise the ideas mentioned about the disease and finally to gradually implement a somatic and psychological rehabilitation program that restores the original way of life as much as possible. .

While other psychological approaches to the CMS are conceivable, the cognitive-behavioral therapy certainly seems promising. An English open study of this treatment in 55 severely disabled patients with CMS resulted in statistically significant and lasting improvements in functioning in 69% of the 32 patients who were willing to have the treatment. 21 For a number of these patients it was a matter of a full recovery of the previous level of functioning. Control group studies into this form of therapy are now being conducted.

CONCLUSION

The chronic tiredness syndrome leads to severe morbidity and has a poor prognosis. Although a considerable amount of research has been done, a convincing somatic explanation for the syndrome is lacking to date. A lot of patients with CMS have a psychiatric disorder, especially a depressive syndrome.

Despite the feelings of powerlessness that patients with CMS evoke in their doctors, their complaints deserve serious attention and every effort should be made to help them. In our view, extensive somatic aid inverstigation is not useful and may be harmful. Antidepressants should be considered when marked major depressive disorder exists. Careful examination of the factors that may maintain the syndrome should precede advice for gradual rehabilitation, requiring comprehensive support and understanding of patients. This approach can certainly be applied by the general practitioner.Referral to a specialist is necessary if the GP does not have sufficient skills or patience or if the patient shows severe psychiatric symptoms or has very persistent ideas about the disease.

Research into the somatic and psychiatric aspects of the CMS should be continued. It is most likely to have meaningful results when it is performed in collaboration between somatic and psychiatric or psychological researchers.

This article was written during the period when Dr. Hawton was working as a Boerhaave Professor of Consultative Psychiatry at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Leiden.

Accepted on July 26th 1991

*Note of translator: The original tekst speaks of “luxerende factoren”, which can be said to correspond with ‘precipitating factors’. However, in dutch “luxerend” explicitly specifies events that provoke a psychiatric disorder, and I didn’t want to translate it in a way that lost the original meaning and context.