Utsikt

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Yes.With the LP, at least, wouldn't any fluctuations happen because you stopped doing the LP and saying "STOP!" effectively and properly, and instead began "doing" ME again?

Yes.With the LP, at least, wouldn't any fluctuations happen because you stopped doing the LP and saying "STOP!" effectively and properly, and instead began "doing" ME again?

With the LP, at least, wouldn't any fluctuations happen because you stopped doing the LP and saying "STOP!" effectively and properly, and instead began "doing" ME again?

Can I copy them to this thread?

So what were the results?

Of 150 DNRS participants, 102 agreed to fill out questionnaires for the research–meaning almost a third declined, for unknown reasons. The respondents were predominantly white women, and the average age was 51. They reported an average of five diagnoses each, with fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, multiple chemical sensitivities, depression, and anxiety among the most common. As Guenter himself noted, these diagnoses were not confirmed. Whether they were rendered by a competent clinician or whether patients diagnosed themselves is unknown.

At three months, six months, and 12 months, respectively, the number of participants responding to the questionnaires dropped to 80, 70, and 64. This represents a fairly high rate of what epidemiologists call “loss to follow up.” A significant rate of loss to follow up is not considered a positive endorsement of an intervention, since people who perceived it to be helpful could be considered more likely to respond. When properly accounted for in statistical analyses, a higher drop-out rate can reduce the apparent benefits attributable to an intervention.

The study’s main outcome measure was the SF-36, a quality of life questionnaire with eight sub-scales. One is the physical function sub-scale that is often used in ME/CFS research; other sub-scales focus on mental health, social function, bodily pain, general health and so on. Since these outcomes are subjective and self-reported, they are prone to significant bias and placebo effects, especially given the intervention’s promises of relief from suffering. With no objective measures in the study, the reported findings are difficult to interpret and cannot be called robust.

The mean scores for all eight sub-scales follow a similar path, a major improvement from baseline to three months, with minimal further changes at six and twelve months. The pattern of eight lines trending upwards in tandem looks impressive on a graph, but there is less here than meets the eye. The analysis seems to have involved averaging the scores received from whichever participants submitted them at any given assessment point. If that’s the case, the apparent improvements in scores could be largely or fully an artifact of the drop-outs.

Let’s say the participants who were most impaired at baseline were more likely to drop-out at subsequent points, a reasonable assumption. Let’s say everyone else stayed the same from baseline through 12 months–no worse, but no better. Given that set of facts, the average mean scores calculated from participants who continued to submit data would rise from baseline even though no individual scored any better.

And what if many or most of the 22 participants who were lost to follow up at three months found DNRS not just useless but actually harmful? What if many or most got worse, as some ME patients have reported after going through the Lighting Process?

Demonstrating an improvement in the mean scores of a shrinking pool of participants tells us little if we know nothing about the many who dropped out. In any event, an improvement in mean scores can be influenced by outliers and reveals nothing about how many individuals improved their scores, and by how much. Perhaps the investigators have individual-level data that would indicate actual improvement in a significant number of individuals. If so, they should share these data as well.

Guenter acknowledged that a trial with a control group would provide more robust information, as would the development of biomarkers to measure the hypothesized changes. All true.

I think of it as roughly the same as political extremism on social media and youtube, the "manosphere", QAnon and so on: because there's demand for it, and it's profitable for some to push it. Rabbit holes feel very comfortable to some.As Guenter himself noted, these diagnoses were not confirmed.

How does pseudo-scientific shit like this keep getting approval and funding?

The editor-in-chief of the Lancet (Richard Horton), famous for having promoted and defended the vaccine MMR paper that launched the modern antivaccine movement, praised the PACE trial for its independence and equipoise, with a team who have made asserted claims for decade that the treatment they developed themselves and had "tested" representing "taking a step back" to see what really works. Despite making money from saying so, and having staked their reputation on it. While he (Horton) was doing a promotional tour for it.Looks like the study just started officially recruiting. Also a major problem-the principal investigator Dr Stein is literally selling brain retraining on her website??? https://www.eleanorsteinmd.ca/

Despite literally saying in the study profile that it is unproven LOL.

Major bias. This study should not be happening.

Is this the same Eleanor Stein that wrote the following factsheet linked to on the DoctorswithME website?Looks like the study just started officially recruiting. Also a major problem-the principal investigator Dr Stein is literally selling brain retraining on her website??? https://www.eleanorsteinmd.ca/

Despite literally saying in the study profile that it is unproven LOL.

Major bias. This study should not be happening.

doctorswith.me

doctorswith.me

ME/CFS is not…

“Functional” or psychosomatic. It is not anxiety or depression, Medically Unexplained Symptoms (MUS), Perplexing/Persistent Physical Symptoms (PPS), Functional Neurological Disorder (FND), Pervasive Refusal Syndrome (PRS), Fabricated or Induced Illness (FII), eating disorder or any other psychological labels.

Differentiating ME/CFS from Psychiatric Disorders by Dr. Eleanor Stein

Seems like it. According to ME-pedia she did a presentation with the same name in 2010. And she says she recovered in ~2017 through neuroplasticity. She had a presentation at a conference in 2018 about the role neuroplasticity might play in ME/CFS.Is this the same Eleanor Stein that wrote the following factsheet linked to on the DoctorswithME website?

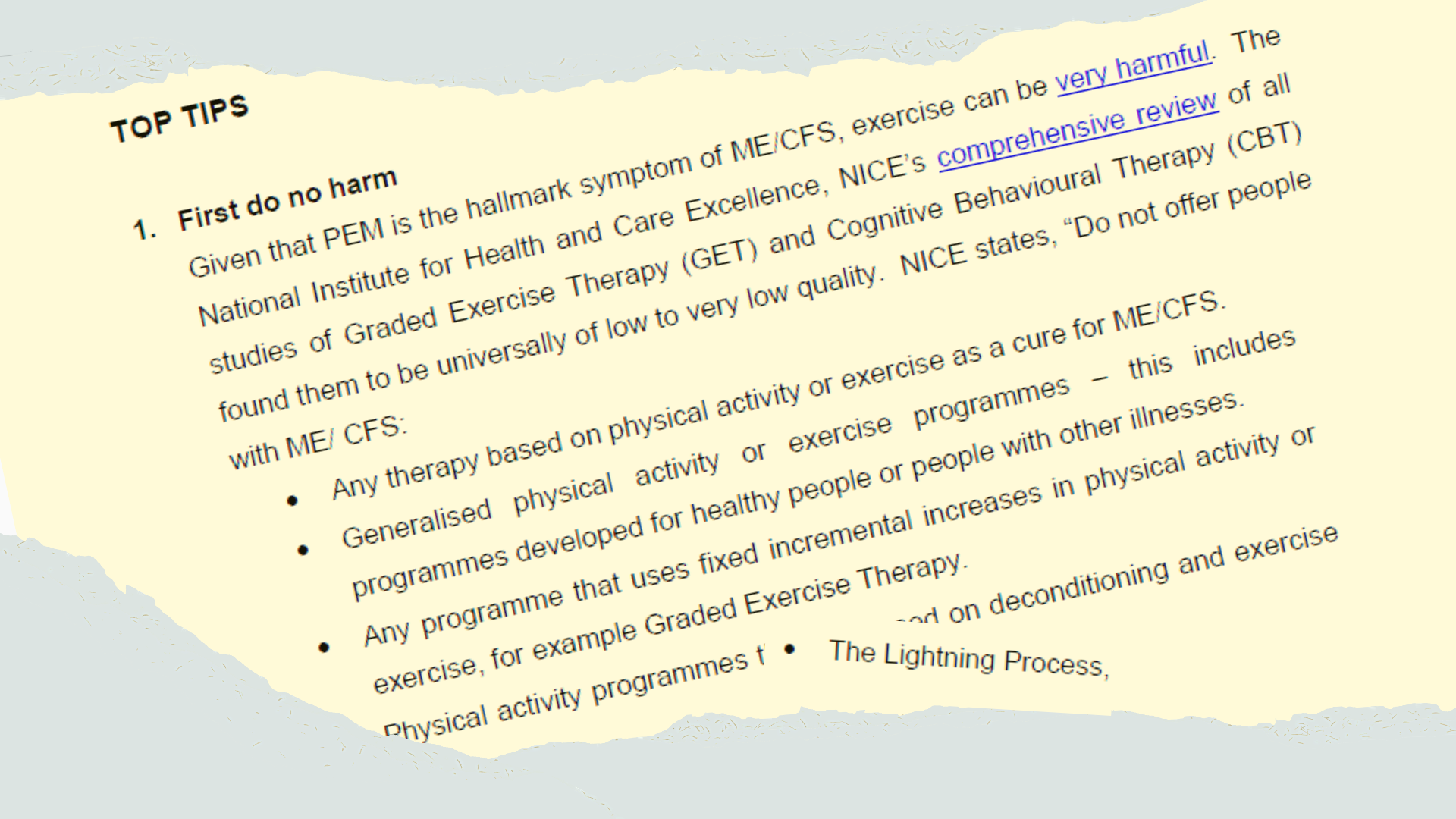

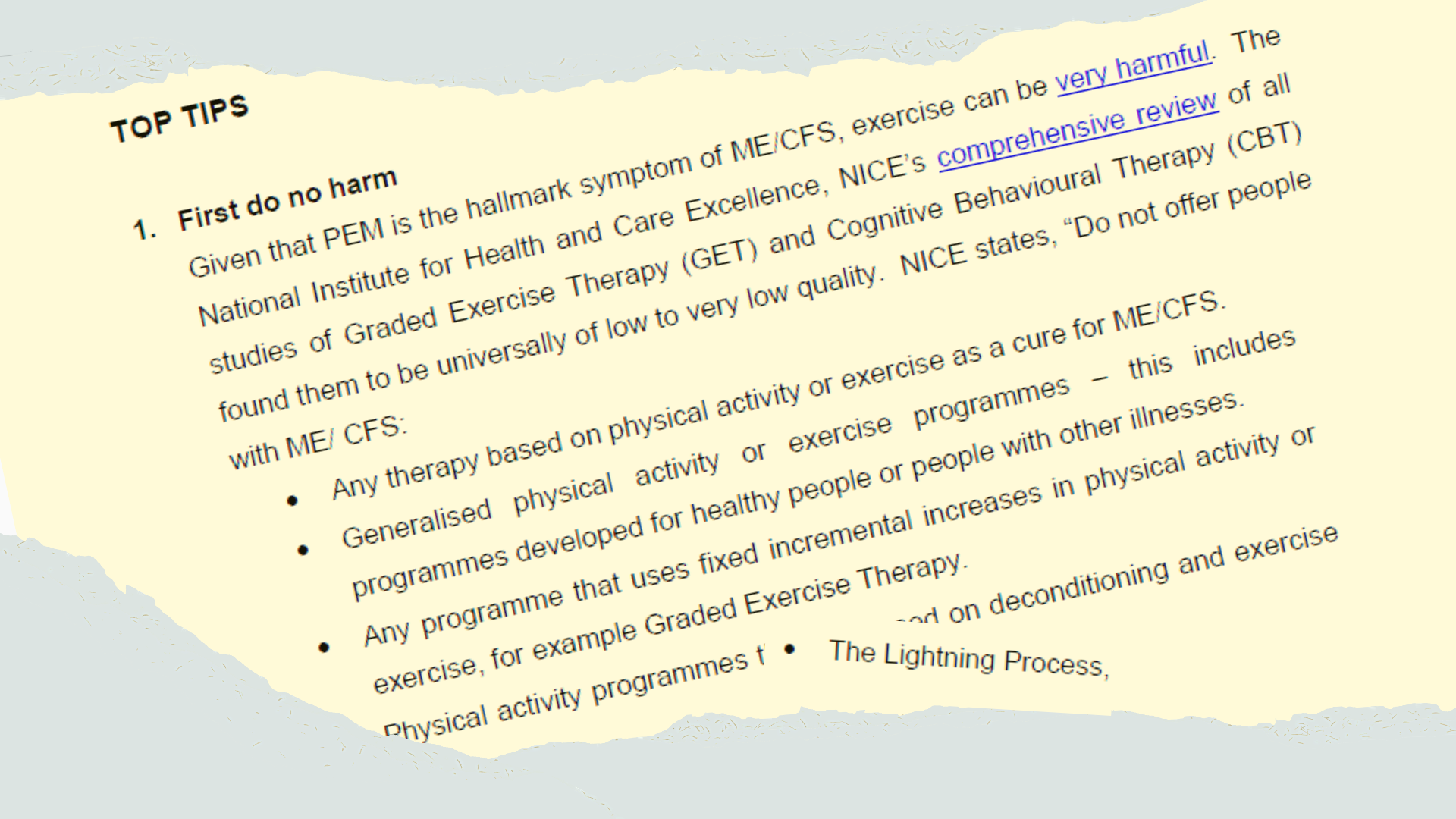

ME/CFS: Top Tips Handout for Doctors

ME/CFS: Top Tips Handout for Doctors - Doctors with M.E.doctorswith.me

Second para down:

Also linked to/referenced in the following sheet: https://doctorswith.me/me-cfs-what-psychiatrists-need-to-know/

I think this is a great idea.Are there any relevant patient charities who can write to the relevant ethics committee and university to explain that this study has too many issues e.g. investigators without equipoise combined with a study design focused on subjective outcomes?

Some objective outcomes have a followup time that is too short to identify deterioration with accumulated exertion. Other objective outcomes provide many opportunities for cherry picking. And there's the track record of the previous study having a very high rate of drop outs.

I wonder if this is a situation where the forum committee could write a letter of concern?

She is also in a video by Raelan Agle who promotes a lot of pseudo BPS crapSeems like it. According to ME-pedia she did a presentation with the same name in 2010. And she says she recovered in ~2017 through neuroplasticity. She had a presentation at a conference in 2018 about the role neuroplasticity might play in ME/CFS.

Eleanor Stein

me-pedia.org

When Sir Simon Wessely, having his tentacles everywhere, can change the content of a book, shouldn't we be able to influence the people who still fund this kind of useless "research"?Just stumbled on this study and thread. The study has too many flaws to be conducted and the waiting list control group. What could go wrong...?

Clinical trials saysClinicalTrials.gov

clinicaltrials.gov

So, it sounds as though recruitment is complete.Primary Completion (Estimated) 2026-04

Study Completion (Estimated) 2027-03