Snow Leopard

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

So why do men have the same second age peak at around 30?

They don't.

https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-014-0167-5

So why do men have the same second age peak at around 30?

According to the recommendations from the Norwegian Directorate of Health, children with suspected CFS/ME should have the diagnosis confirmed by a pediatrician [2]. Thus, children receiving the diagnosis of CFS/ME are routinely referred to their local hospital for the diagnostic work-up.

Adults may receive a diagnosis of CFS/ME after evaluation by a general practitioner.

Young women have previously been reported as the predominant group infected during a waterborne giardiasis outbreak, due to elevated water consumption. Here, the demographics of those subsequently infected are described, and young women again predominate.

I would think that being the largest effort of its kind, the IOM report would likely be the most accurate.I’m wondering - taking into account that all of the statistics for this disease are fairly unreliable since studies are small, definitions differ, etc., which statistics do you all consider the most reliable? I am always uncomfortable quoting almost all of them.

I do believe, for example, that there are more women with this disease than men since every study indicates that and it’s consistent with other immune-related diseases, but I’m uncomfortable with the percentages.

How close are we to accurate on any of the stats?

I would think that being the largest effort of its kind, the IOM report would likely be the most accurate.

Which does not mean it is entirely accurate but likely the most. There is consistency around those numbers as well so if they are off it's likely to not be by much in %.

I agree. I never fully understood where those prevalence figures came from. The article of Jason that is referenced is just a short overview of CFS prevalence in the CFIDS Chronicle.that 2.5M upper prevalence for ME/CFS appears to be an error in the report.

Isn't 2.5 million equivalent to the 0.82% (or thereabouts) from the 'CFS-like' figure?I agree. I never fully understood where those prevalence figures came from. The article of Jason that is referenced is just a short overview of CFS prevalence in the CFIDS Chronicle.

There are some (rather misleading) studies such as the CDC Georgia study and Wessely's prevalence study in the UK that reported a much higher prevalence of 2,5%. But given that there are approximately 300 million Americans, that would lead to an estimated higher bound of 7,5 million. So that can't be where the 2,5 million came from. I also don't see how it could refer to the CFS-like patients in the 1999 Chicago study. Anyone else has a clue from which study the 2,5 million figure comes?

Even the lower bound of 836.000 is strange. It's the figure the Chicago study reported. But that was in 1999, there are approximately 500.000 Americans more now. Also this prevalence study gave a figure of 0,42% which is higher than the 0,23% (Reyes et al. 2003) or 0,19% (Nacul et al. 2011)study reported, so why should it be used as a lower boundary?

In my view, they should have said that ME/CFS has an estimated prevalence of 0,2%-0,4% and then calculated how many Americans that would be for the current US population (the prevalences are for adult populations only, If I'm not mistaken).

Where does the 0,82% figure come from?Isn't 2.5 million equivalent to the 0.82% (or thereabouts) from the 'CFS-like' figure?

Isn't 2.5 million equivalent to the 0.82% (or thereabouts) from the 'CFS-like' figure?

The Georgia study used the overly broad Reeves criteria that included "unwellness" and more mental illness and as a result inflated prevalence 10 fold over CDC's own previous estimates.There are some (rather misleading) studies such as the CDC Georgia study and Wessely's prevalence study in the UK that reported a much higher prevalence of 2,5%.

The Nacul study reported 0.19% for Fukuda but only 0.11% for Canadian so perhaps the lower range should be even lower. In reality, we have no idea because much of the epi research is so flawed. In the meantime and at least in the US, the 0.42% estimate from Jason's study has tended to be the most accepted estimate.Even the lower bound of 836.000 is strange. It's the figure the Chicago study reported. But that was in 1999, there are approximately 500.000 Americans more now. Also this prevalence study gave a figure of 0,42% which is higher than the 0,23% (Reyes et al. 2003) or 0,19% (Nacul et al. 2011)study reported, so why should it be used as a lower boundary?

In my view, they should have said that ME/CFS has an estimated prevalence of 0,2%-0,4% and then calculated how many Americans that would be for the current US population (the prevalences are for adult populations only, If I'm not mistaken).

Ok, but where does that figure come from, which study is it based on?2.5M is CDC's report of "CFS-like" illness.

I can't remember. I thought it was due to a doubling of one of other numbers as a guesstimate.Where does the 0,82% figure come from?

The prevalence rates are estimates from studies in adults so 2.5M would equate to about .99% of the current adult US population. There are few studies in children but the prevalence estimates are much lower, particularly in children under 10-12.Where does the 0,82% figure come from?

Ok, but where does that figure come from, which study is it based on?

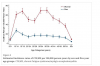

Read on. Not sure what the adjustment for population figures was.According to figure 1 they do.

Figure 3 shows the estimated incidence rate per 100,000 person years for men and women separately. After adjustment for population figures, the pattern with two age peaks is clear for women, whereas a second peak is not evident for men.

Given some of the ME/CFS criteria require children only need be ill for 3 months to be diagnosed and given the Norwegian children seem to be diagnosed in a hospital clinic, they are more likely to have shown up in the NPR (hospital) database quickly. In contrast, the adults need to have been ill for 6 months before diagnosis and then they can be diagnosed by a GP. They might undergo some evaluations in the hospital but might not be given a diagnosis there. Therefore they may take much longer to show up in the NPR database with a diagnosis of ME/CFS. Some of those adults may recover from their post-viral fatigue illness and never be recorded in the Norway Patient register as having ME/CFS, whereas the children who recover quickly probably are recorded.

Maybe the way to think about the incidence in women is to consider that there’s a dip in incidence in your 20s, rather than two peaks, one in your teens and one in your thirties....

So perhaps there is something protective going on in your 20s, when you are ‘in your prime’? And if you are genetically susceptible, then you will mostly have succumbed by your forties....?

Thread here:Another 2.4 year prospective study. (mean baseline age of entire population was 44.9, 57% women)

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3427300

New onset 0.08%/year, mean age of 48.0. 56% of new cases were women.

"Lifetime diagnosis at baseline" was 1.3%. (note this was self-reported)

New onset 0.08%/year, mean age of 48.0. 56% of new cases were women.