Fluid transport in the brain

The brain harbors a unique ability to, figuratively speaking, shift its gears. During wakefulness, the brain is geared fully toward processing information and behaving, while homeostatic functions predominate during sleep. The blood-brain barrier establishes a stable environment that is optimal for neuronal function, yet the barrier imposes a physiological problem; transcapillary filtration that forms extracellular fluid in other organs is reduced to a minimum in brain. Consequently, the brain depends on a special fluid [the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)] that is flushed into brain along the unique perivascular spaces created by astrocytic vascular endfeet.

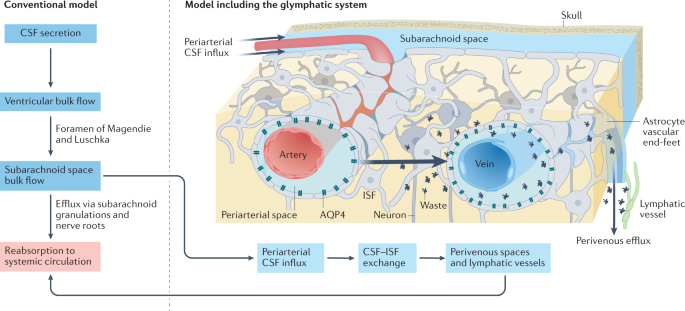

We describe this pathway, coined the term glymphatic system, based on its dependency on astrocytic vascular endfeet and their adluminal expression of aquaporin-4 water channels facing toward CSF-filled perivascular spaces. Glymphatic clearance of potentially harmful metabolic or protein waste products, such as amyloid-β, is primarily active during sleep, when its physiological drivers, the cardiac cycle, respiration, and slow vasomotion, together efficiently propel CSF inflow along periarterial spaces. The brain’s extracellular space contains an abundance of proteoglycans and hyaluronan, which provide a low-resistance hydraulic conduit that rapidly can expand and shrink during the sleep-wake cycle.

We describe this unique fluid system of the brain, which meets the brain’s requisites to maintain homeostasis similar to peripheral organs, considering the blood-brain-barrier and the paths for formation and egress of the CSF.

Web | DOI | PDF | Physiological Reviews | Open Access

Martin Kaag Rasmussen; Humberto Mestre; Maiken Nedergaard

The brain harbors a unique ability to, figuratively speaking, shift its gears. During wakefulness, the brain is geared fully toward processing information and behaving, while homeostatic functions predominate during sleep. The blood-brain barrier establishes a stable environment that is optimal for neuronal function, yet the barrier imposes a physiological problem; transcapillary filtration that forms extracellular fluid in other organs is reduced to a minimum in brain. Consequently, the brain depends on a special fluid [the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)] that is flushed into brain along the unique perivascular spaces created by astrocytic vascular endfeet.

We describe this pathway, coined the term glymphatic system, based on its dependency on astrocytic vascular endfeet and their adluminal expression of aquaporin-4 water channels facing toward CSF-filled perivascular spaces. Glymphatic clearance of potentially harmful metabolic or protein waste products, such as amyloid-β, is primarily active during sleep, when its physiological drivers, the cardiac cycle, respiration, and slow vasomotion, together efficiently propel CSF inflow along periarterial spaces. The brain’s extracellular space contains an abundance of proteoglycans and hyaluronan, which provide a low-resistance hydraulic conduit that rapidly can expand and shrink during the sleep-wake cycle.

We describe this unique fluid system of the brain, which meets the brain’s requisites to maintain homeostasis similar to peripheral organs, considering the blood-brain-barrier and the paths for formation and egress of the CSF.

Web | DOI | PDF | Physiological Reviews | Open Access