Fatigue in children and young people up to 24 months after infection with SARS-CoV-2

Persistent fatigue is common following acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. Little is known about post-infection fatigue trajectories in children and young people (CYP). This paper reports on a longitudinal analysis of the Children and Young People with Long COVID study. SARS-CoV-2-positive participants, aged 11-to-17-years at enrolment, responding to follow-ups at 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-months post-infection were included.

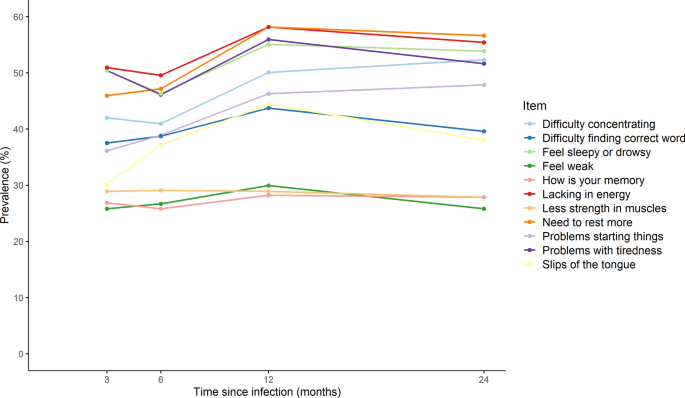

Fatigue was assessed via the Chalder Fatigue Scale (CFQ; score range: 0-11, with ≥4 indicating clinical case-ness) and by a single-item (no, mild, severe fatigue). Fatigue was described cross-sectionally and examined longitudinally using linear mixed-effects models.

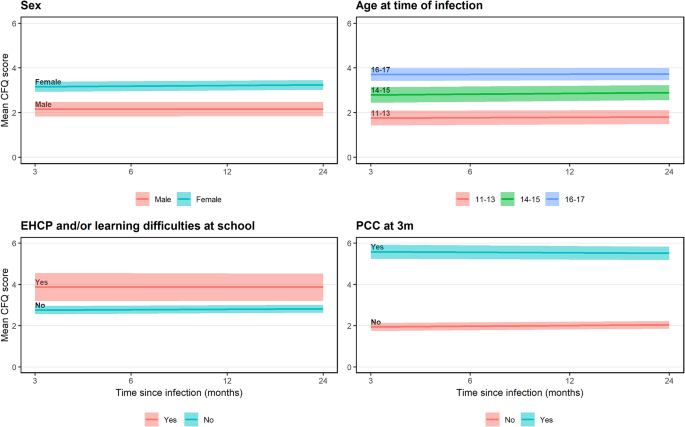

Among 943 SARS-CoV-2-positive participants, 581 (61.6%) met CFQ case-ness at least once during follow-up. A higher proportion of ever-cases (vs. never-cases) were female (77.1% vs. 54.4%), older (mean age 15.0 vs. 13.9 years), and met Post-COVID Condition criteria 3-months post-infection (35.6% vs. 7.2%). The proportion of CFQ cases increased from 35.0% at 3-months to 40.2% at 24-months post-infection; 15.9% meet case-ness at all follow-ups. Single-item mild/severe responses showed sensitivity (≥0.728) and specificity (≥0.755) for CFQ case ascertainment. On average, CFQ scores increased by 0.448 points (95% CI, 0.252 to 0.645) over 24-months, but there were subgroup differences (e.g., fatigue increased faster in females than males and improved slightly in those meeting Post-COVID Condition criteria 3-months post-infection while worsening in those not meeting criteria).

Persistent fatigue was prominent in CYP up to 24 months after infection. Subgroup differences in scores and trajectories highlight the need for targeted interventions. Single-item assessment is a practical tool for screening significant severe fatigue.

Web | DOI | PDF | Nature Scientific Reports | Open Access

Richards-Belle, Alvin; Shafran, Roz; Rojas, Natalia K; Stephenson, Terence; Carr, Ewan; Chalder, Trudie; Dalrymple, Emma; McOwat, Kelsey; Simmons, Ruth; Pinto Pereira, Snehal M

Persistent fatigue is common following acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. Little is known about post-infection fatigue trajectories in children and young people (CYP). This paper reports on a longitudinal analysis of the Children and Young People with Long COVID study. SARS-CoV-2-positive participants, aged 11-to-17-years at enrolment, responding to follow-ups at 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-months post-infection were included.

Fatigue was assessed via the Chalder Fatigue Scale (CFQ; score range: 0-11, with ≥4 indicating clinical case-ness) and by a single-item (no, mild, severe fatigue). Fatigue was described cross-sectionally and examined longitudinally using linear mixed-effects models.

Among 943 SARS-CoV-2-positive participants, 581 (61.6%) met CFQ case-ness at least once during follow-up. A higher proportion of ever-cases (vs. never-cases) were female (77.1% vs. 54.4%), older (mean age 15.0 vs. 13.9 years), and met Post-COVID Condition criteria 3-months post-infection (35.6% vs. 7.2%). The proportion of CFQ cases increased from 35.0% at 3-months to 40.2% at 24-months post-infection; 15.9% meet case-ness at all follow-ups. Single-item mild/severe responses showed sensitivity (≥0.728) and specificity (≥0.755) for CFQ case ascertainment. On average, CFQ scores increased by 0.448 points (95% CI, 0.252 to 0.645) over 24-months, but there were subgroup differences (e.g., fatigue increased faster in females than males and improved slightly in those meeting Post-COVID Condition criteria 3-months post-infection while worsening in those not meeting criteria).

Persistent fatigue was prominent in CYP up to 24 months after infection. Subgroup differences in scores and trajectories highlight the need for targeted interventions. Single-item assessment is a practical tool for screening significant severe fatigue.

Web | DOI | PDF | Nature Scientific Reports | Open Access