JaimeS

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

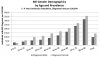

Other data and clinical experience indicates that the gender difference emerges during adolescence and remains at around 3:1, and that peak incidence years are the teens and the 30s. ME/CFS is rarely diagnosed in people over the age of 65 because there are so many other potential causes of the symptoms.

By contrast, the graph implies* peak incidence from age 60, not in adolescent years and people‘s 30s. And only a modest female bias.

* The big jumps in prevalence indicate high rates of incidence

I think that, unfortunately, this is a case of garbage in, garbage out.

We're not looking at age of onset here, we're looking at prevalence. So to me, it absolutely makes sense that as more people are diagnosed and do not die, the incidence should increase with each decade of life.

We have some evidence of earlier mortality, but it is quite preliminary.