Andy

Senior Member (Voting rights)

Rintatolimod = Ampligen

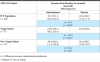

Open access, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0240403A hypothesis-based post-hoc analysis of the Intent to Treat (ITT) population diagnosed with ME/CFS from 12 independent clinical sites of a Phase III trial was performed to evaluate the effect of rintatolimod therapy based on disease duration. The clinical activity of rintatolimod was evaluated by exercise treadmill tolerance (ETT) using a modified Bruce protocol. The ITT population (n = 208) was divided into two subsets of symptom duration. Patients with symptom duration of 2–8 years were identified as the Target Subset (n = 75); the remainder (<2 year plus >8 year) were identified as the Non-Target Subset (n = 133). Placebo-adjusted percentage improvements in exercise duration and the vertical rise for the Target Subset (n = 75) were more than twice that of the ITT population. The Non-Target Subset (n = 133) failed to show any clinically significant ETT response to rintatolimod when compared to placebo. Within the Target Subset, 51.2% of rintatolimod-treated patients improved their exercise duration by ≥25% (p = 0.003) despite reduced statistical power from division of the original ITT population into two subsets.

Conclusion/significance

Analysis of ETT from a Phase III trial has identified within the ITT population, a subset of ME/CFS patients with ≥2 fold increased exercise response to rintatolimod. Substantial improvement in physical performance was seen for the majority (51.2%) of these severely debilitated patients who improved exercise duration by ≥25%. This magnitude of exercise improvement was associated with clinically significant enhancements in quality of life. The data indicate that ME/CFS patients have a relatively short disease duration window (<8 years) to expect a significant response to rintatolimod under the dosing conditions utilized in this Phase III clinical trial. These results may have direct relevance to the cognitive impairment and fatigue being experienced by patients clinically recovered from COVID-19 and free of detectable SARS-CoV-2.