I know. The only relevant study I know of,

Schachterle et al. 2004, frames it similarly, all about fearful females that can be reassured by physicians.

I wonder do men with ME/CFS who are considering fatherhood get a mention in Spickett's book?

He was my consultant, don't have the brain or energy to go into it, but royally pissed off he thinks he's in any position of writing about diagnosis and management, to be fair I haven't read what he's written, particularly about severe m.e., he's been retired for years and I can only hope whatever knowledge/experience he thinks he has has come from deep reflection and regret, are we to expect more of this now decode has made us relevant?

Oh Beth, I'm sorry. I would feel the same if the doctor who said to me "You could always have a baby. Some women feel better during pregnancy." wrote a book. I remember trying to talk with him about the aftermath of said pregnancy, i.e. a little human needing care that I knew I could not provide, and he just looked at me like I was a weirdo.

This! And while yes, sure we did wonder if my ME would be an issue during pregnancy, there wasn't exactly any evidence to guide us to make a decision either way.

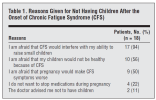

Yeah, and look, we're not alone, in the

Schachterle et al. 2004 study, the most common reason for not having children was

a fear of judging that they wouldn't be able to raise them:

I'm so glad you managed to have a child,

@Midnattsol and that it has worked out OK for you. I have watched your story and was so happy for you and your partner that you went for it and that it worked.

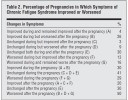

I had to make the opposite decision with my husband, unfortunately. And it was the right one, as I continued to deteriorate for 10 solid years, but a very hard one. If we had had a child, I think it's likely I'd be very severe rather than severe, and it's possible the marriage would not have survived because of the strain on my husband who would have essentially become a single father while trying to be the breadwinner and somehow provide care for me. And our much-wanted and much-loved child(ren) would not have had the life we would have wanted them to have at all. Unless I was in the lucky 7% (A+C in table 2 below) who improved after the pregnancy, it just would not have worked for us. (Am not including F because they may only have improved back to where they started.) If my ME/CFS had been stable rather than constantly deteriorating, we would have made a different decision.

But of course, it's also possible things would have worked out much better. There are plenty of people with ME/CFS, including severe ME/CFS, who have children (though I think usually they were less severe when they had them) and they've managed well.

[Table from

Schachterle et al. 2004]

I don't like that people looking at

Schachterle et al., whether women/couples trying to decide or health professionals advising them, are likely to see this is the abstract and not notice the error:

Schachterle et al. 2004 said:

After pregnancy, there was no change in CFS symptoms in 21 (30%), an improvement of symptoms in 14 (20%), and a worsening of symptoms in 35 (20%) of the subjects [should read "worsening of symptoms in 50%" as per table 2 above].

I find there is far too much emphasis on reassuring presumed fearful females, and too little on gathering good quality data that could help women

and men who are considering having children to make the decision that's right for them.

I don't find it particularly reassuring that:

Schachterle et al. 2004 said:

In summary, this study did not find evidence that pregnancy worsens the symptoms of CFS in most women.

when they found that 50% were worse afterwards.