Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial on the Efficacy of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure and Adaptive Servo-Ventilation in the Treatment of Chronic Complex Insomnia

Barry Krakow, Natalia D. McIver, Victor A. Ulibarri, Jessica Krakow, Ronald M. Schrader

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(19)30104-X/fulltext (PDF available)

Background

Complex insomnia, the comorbidity of chronic insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), is a common sleep disorder, but the OSA component, whether presenting overtly or covertly, often goes unsuspected and undiagnosed due to a low index of suspicion. Among complex insomniacs, preliminary evidence demonstrates standard CPAP decreases insomnia severity. However, CPAP causes expiratory pressure intolerance or iatrogenic central apneas that may diminish its use. An advanced PAP mode—adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV)—may alleviate CPAP side-effects and yield superior outcomes.

Methods

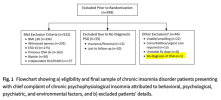

In a single-site protocol investigating covert complex insomnia (

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier:

NCT02365064), a low index of suspicion for this comorbidity was confirmed by exclusion of 455 of 660 eligible patients who presented during the study period with overt OSA signs and symptoms. Ultimately, stringent inclusion/exclusion criteria to test efficacy yielded 40 adult, covert complex insomnia patients [average Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) moderate–severe 19.30 (95% CI 18.42–20.17)] who reported no definitive OSA symptoms or risks and who failed behavioral or drug therapy for an average of one decade. All 40 were diagnosed with OSA and randomized (using block randomization) to a single-blind, prospective protocol, comparing CPAP (n = 21) and ASV (n = 19). Three successive PAP titrations fine-tuned pressure settings, facilitated greater PAP use, and collected objective sleep and breathing data. Patients received 14 weeks of treatment including intensive biweekly coaching and follow-up to foster regular PAP use in order to accurately measure efficaciousness. Primary outcomes measured insomnia severity and sleep quality. Secondary outcomes measured daytime impact: OSA-induced impairment, fatigue severity, insomnia impairment, and quality of life. Performance on these seven variables was assessed using repeated measures ANCOVA to account for the multiple biweekly time points.

Findings

At intake, OSA diagnosis and OSA as a cause for insomnia were denied by all 40 patients, yet PAP significantly decreased insomnia severity scores (p = 0.021 in the primary ANCOVA analysis). To quantify effect sizes, mean intake vs endpoint analysis was conducted with ASV yielding nearly twice the effects of CPAP [−13.2 (10.7–15.7), Hedges' g = 2.50 vs −9.3 (6.3–12.3), g = 1.39], and between mode effect size was in the medium-large range 0.65. Clinically, ASV led to remission (ISI < 8) in 68% of cases compared to 24% on CPAP [Fisher's exact p = 0.010]. Two sleep quality measures in the ANCOVA analysis again demonstrated superior significant effects for ASV compared to CPAP (both p < 0.03), and pre- and post-analysis demonstrated substantial effects for both scales [ASV (g = 1.42; g = 1.81) over CPAP (g = 1.04; g = 0.75)] with medium size effects between modes (0.54, 0.51). Measures of impairment, residual objective sleep breathing events, and normalized breathing periods consistently demonstrated larger beneficial effects for ASV over CPAP.

Interpretation

PAP therapy was highly efficacious in decreasing insomnia severity in chronic insomnia patients with previously undiagnosed co-morbid OSA. ASV proved superior to CPAP in this first efficacy trial to compare advanced to traditional PAP modes in complex insomnia. Future research must determine the following: pathophysiological mechanisms to explain how OSA causes chronic insomnia; general population prevalence of this comorbidity; and, cost-effectiveness of ASV therapy in complex insomnia. Last, efforts to raise awareness of complex insomnia are urgently needed as patients and providers appear to disregard both overt and covert signs and symptoms of OSA in the assessment of chronic insomnia.