Andy

Senior Member (Voting rights)

Abstract

Ewing sarcoma is the second most frequent primary bone tumour of childhood and adolescence. The aim of this report is to describe the imaging, pathology, clinical findings, and treatment of a primary intradural extramedullary Ewing sarcoma with a unique intracranial metastatic component in a pediatric patient. A 14-year-old girl with a history of mood disorders presented to the emergency department with a 3-week history of neck torticollis, cervical pain, paresis, and paresthesia of the upper and lower extremities on the left side. Initially, non-organic causes such as somatization or conversion disorder were suspected. She returned 3 months later when her symptoms worsened.

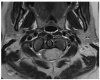

MRI of the head and spine was performed, and demonstrated the presence of a suprasellar, retro-chiasmatic mass lesion. There was also diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement, another well-defined intradural extramedullary lesion the sacral region and several multifocal cauda equina soft tissue nodules.

The patient first underwent surgery. The patient was also treated with a combination of chemotherapy (vincristine, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide alternating with ifosfamide and etoposide (VDC/IE)) and radiation as per the Children's Oncology Group AEWS1221 protocol. Most recent imaging conducted 22 months after the initial mass discovery revealed improvement of the suprasellar mass lesion with residual stable appearance of the prominence and enhancement of the pituitary stalk and tuber cinereum. There was interval improvement of the spinal lesions with no convincing residual.

Clinically, at almost three years since initial imaging findings, and 25 months since completing treatment, she is stable from an oncology perspective.

Open access, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1930043324001912

Ewing sarcoma is the second most frequent primary bone tumour of childhood and adolescence. The aim of this report is to describe the imaging, pathology, clinical findings, and treatment of a primary intradural extramedullary Ewing sarcoma with a unique intracranial metastatic component in a pediatric patient. A 14-year-old girl with a history of mood disorders presented to the emergency department with a 3-week history of neck torticollis, cervical pain, paresis, and paresthesia of the upper and lower extremities on the left side. Initially, non-organic causes such as somatization or conversion disorder were suspected. She returned 3 months later when her symptoms worsened.

MRI of the head and spine was performed, and demonstrated the presence of a suprasellar, retro-chiasmatic mass lesion. There was also diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement, another well-defined intradural extramedullary lesion the sacral region and several multifocal cauda equina soft tissue nodules.

The patient first underwent surgery. The patient was also treated with a combination of chemotherapy (vincristine, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide alternating with ifosfamide and etoposide (VDC/IE)) and radiation as per the Children's Oncology Group AEWS1221 protocol. Most recent imaging conducted 22 months after the initial mass discovery revealed improvement of the suprasellar mass lesion with residual stable appearance of the prominence and enhancement of the pituitary stalk and tuber cinereum. There was interval improvement of the spinal lesions with no convincing residual.

Clinically, at almost three years since initial imaging findings, and 25 months since completing treatment, she is stable from an oncology perspective.

Open access, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1930043324001912