Evergreen

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Gotcha.No, I am saying I am suspicious because

1. There is no baseline pre run in measurement, for both groups, whereas in Dara we know the run in baselines for 90 days.

2. There is no data on the severity of these patients pre treatment, whereas in Dara we know severity pre treatment. By severity, I mean step count, not survey score.

3. The step counts were recorded for a period of 4-6 days, in contrast to a period of 9 months pre and post treatment in Dara.

I don't think these things matter as much as we might think they would.

The part of the placebo response that is drug-related starts when the drug starts (unless the participants know the drug would not be expected to have an effect till X weeks). The run-in data is still useful to have, but it's not relevant for the point we're debating here.

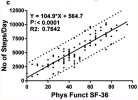

It's true that we don't have baseline step counts for ritux in the phase II trial, but we do know that the responders were a little, but not a lot, less severe than the non-responders (mean SF36 PF at baseline 42.9 vs 36.5, table 4), and steps per day correlate well with SF36 PF (van Campen et al. 2020).

Continuous measurement is likely to give more representative data for individuals, but when we're comparing group means to determine if something is effective or not, I'm not sure there'll be an advantage over shorter-term measurements.

None of these points can explain normal or near-normal step counts of responders in the phase II rituximab trial. But the placebo response can.

Editing to add this graph from van Campen et al. 2020:

Last edited by a moderator: