Andy

Senior Member (Voting rights)

Full title: Evaluation of a Multidisciplinary Integrated Treatment Approach Versus Standard Model of Care for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (FGIDS): A Matched Cohort Study

Abstract

Background

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID) are linked to a variety of potential causes, and treatments include reassurance, life-style (including diet), psychological, or pharmacologic interventions.

Aims

To assess whether a multidisciplinary integrated treatment approach delivered in a dedicated integrated care clinic (ICC) was superior to the standard model of care in relation to the gastrointestinal symptom burden.

Methods

A matched cohort of 52 consecutive patients with severe manifestation of FGID were matched with 104 control patients based upon diagnosis, gender, age, and symptom severity. Patients in the ICC received structured assessment and 12-weeks integrated treatment sessions provided as required by gastroenterologist and allied health team. Control patients received standard medical care at the same tertiary center with access to allied health services as required but no standardized interprofessional team approach. Primary outcome was reduction in gastrointestinal symptom burden as measured by the Structured Assessment of Gastrointestinal Symptoms Scale (SAGIS). Secondary outcome was reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

Results

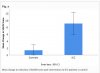

Mixed models estimated the within ICC change in SAGIS total as −9.7 (95% CI −13.6, −5.8; p < 0.0001), compared with −1.7 (95% CI −4.0, 0.6; p = 0.15) for controls. The difference between groups reached statistical significance, −7.6 (95% CI −11.4, −3.8; p < 0.0001). Total HADS scores in ICC patients were 3.4 points lower post-intervention and reached statistical significance (p = 0.001).

Conclusion

This matched cohort study demonstrates superior short-term outcomes of FGID patients in a structured multidisciplinary care setting as compared to standard care.

Open access, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10620-022-07464-1

Abstract

Background

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID) are linked to a variety of potential causes, and treatments include reassurance, life-style (including diet), psychological, or pharmacologic interventions.

Aims

To assess whether a multidisciplinary integrated treatment approach delivered in a dedicated integrated care clinic (ICC) was superior to the standard model of care in relation to the gastrointestinal symptom burden.

Methods

A matched cohort of 52 consecutive patients with severe manifestation of FGID were matched with 104 control patients based upon diagnosis, gender, age, and symptom severity. Patients in the ICC received structured assessment and 12-weeks integrated treatment sessions provided as required by gastroenterologist and allied health team. Control patients received standard medical care at the same tertiary center with access to allied health services as required but no standardized interprofessional team approach. Primary outcome was reduction in gastrointestinal symptom burden as measured by the Structured Assessment of Gastrointestinal Symptoms Scale (SAGIS). Secondary outcome was reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

Results

Mixed models estimated the within ICC change in SAGIS total as −9.7 (95% CI −13.6, −5.8; p < 0.0001), compared with −1.7 (95% CI −4.0, 0.6; p = 0.15) for controls. The difference between groups reached statistical significance, −7.6 (95% CI −11.4, −3.8; p < 0.0001). Total HADS scores in ICC patients were 3.4 points lower post-intervention and reached statistical significance (p = 0.001).

Conclusion

This matched cohort study demonstrates superior short-term outcomes of FGID patients in a structured multidisciplinary care setting as compared to standard care.

Open access, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10620-022-07464-1