Hi and welcome to the forum,

@Shiqiru !

The medrxiv formatting is quite difficult to read - I have never understood why they insist on doing it that way. So this might already have been covered in the preprint and I just was unable to find it, but I’m wondering if you could elaborate on which patients you believe this test might be useful for? Long covid is a very broad label that covers anything from critical ICU patients with severe lung damage to someone with just loss of smell 3 months after covid.

PS. Would you be able to add line breaks between the paragraphs in the posts? Many pwME/CFS (including myself) struggle with blocks of text and have to consume written materials in small chunks at a time.

My apologies, I did not include line breaks in my previous response. Thank you very much for the reminder; this is invaluable feedback for me.

A Layman's Explanation of Pulmonary Oxygen Reserve Capacity (ORC):

What is Pulmonary Oxygen Reserve Capacity?

Simply put, it measures your lungs' ability to effectively absorb and deliver oxygen to the bloodstream even when oxygen supply is insufficient (e.g., at high altitudes). It's an indicator of the "redundancy" or "elasticity" of lung function. Just as Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing (CPET) and the 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) assess how the body utilizes this "redundancy" and "elasticity" of the lungs through exercise, the ORC test evaluates it under low-oxygen conditions.

Regarding "Which patients are suitable for ORC testing" and "The broadness of the Long COVID label":

You are absolutely correct that "Long COVID is a very broad label," and not all individuals with Long COVID necessarily experience impaired pulmonary oxygen reserve capacity. However, from our research perspective, as a respiratory infectious disease (and similarly for other respiratory conditions):

Acute Phase: During the acute phase, both severe and mild cases may exhibit a decrease in pulmonary oxygen reserve capacity (ORC), with ORC potentially even becoming negative in severe instances.

Chronic Phase: While symptoms in the chronic phase are diverse, a significant proportion of patients presenting with core symptoms such as fatigue, dyspnea (shortness of breath), and exercise intolerance are highly likely to have abnormalities related to their ORC.

How is the ORC Test Measured, and What are its Units?

The ORC test identifies the critical inspired oxygen concentration at which your blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) begins to fall below 90%.

A lower inspired oxygen concentration at this threshold indicates better pulmonary oxygen reserve capacity.

We quantify this using the formula ORC = 21% - FiO2-MIN, where 21% represents the oxygen concentration in ambient air (21%), and FiO2-MIN is the minimum inspired oxygen fraction when SpO2 drops to 90%. Consequently, the ORC value is expressed as a percentage.

We can draw an analogy with altitude, as higher altitudes naturally entail lower oxygen concentrations:

For a healthy individual at rest, their blood oxygen (SpO2) might remain around 95% (normal) up to approximately 2900 meters (around 9500 feet). If SpO2 begins to drop below 90% at roughly 3000 meters (corresponding to about 15.5% oxygen concentration), their calculated ORC value (via the formula) would be approximately 5.5%.

Conversely, if a patient (e.g., during an acute infection or with pre-existing pulmonary impairment) experiences an SpO2 drop below 90% at an altitude of only 1900 meters (around 6200 feet, corresponding to about 17.2% oxygen concentration), their calculated ORC value would be around 3.8%.

This means that this patient's pulmonary oxygen reserve capacity has decreased by an extent equivalent to 1100 meters of altitude compared to their healthy state. The ORC value has decreased from a healthy 5.5% to 3.8%, a reduction of 1.7 percentage points. This quantitatively indicates an increase in symptom severity, as a lower ORC value signifies more compromised lung function.

Why is ORC Crucial for ME/CFS and Long Covid?

Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) frequently suffer from debilitating fatigue, post-exertional malaise (PEM), dyspnea, and exercise intolerance. These pervasive symptoms are intrinsically linked to the body's capacity to acquire and efficiently utilize oxygen. The ORC test offers an objective and quantitative metric that directly reflects the extent of impairment in this crucial physiological function, thereby providing a measurable biological underpinning for these core symptoms.

Pulmonary Oxygen Reserve Capacity (ORC) Testing vs. CPET and 6MWT:

While CPET (Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing) and 6MWT (6-Minute Walk Test) also provide insights into the body's oxygen utilization capacity, they differ significantly from the ORC test.

CPET and 6MWT evaluate the body's maximal oxygen consumption or exercise endurance by varying physical exertion. They primarily reflect the overall performance of the body's energy systems during an active state.

In contrast, the ORC test assesses this by precisely controlling the inspired oxygen concentration. Its primary focus is on the lungs' adaptive capacity to varying oxygen levels, while also stabilizing pulmonary ventilation changes and eliminating confounding effects typically associated with physical activity.

Advantages of the ORC Test:

Higher Sensitivity: In the 6MWT, many individuals with compromised oxygen reserve capacity may not exhibit a noticeable drop in blood oxygen levels after walking, which can limit the test's diagnostic value. (I believe many 6MWT participants can attest to this experience.) The ORC test, however, can detect subtle reductions in pulmonary oxygen reserve capacity much earlier and with greater precision.

Objective and Quantitative: Any change in ORC is directly reflected and quantified by the ORC test, providing measurable data.

Simpler and More Convenient: Performed in a resting state, the ORC test eliminates the need for strenuous exercise. Its relatively simple equipment also significantly reduces the burden on patients.

Real-world Case Studies:

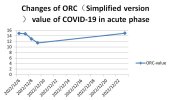

My Wife's Acute COVID-19 ORC Test Curve: On December 6, 2022, my wife tested weakly positive for COVID-19. We initiated simplified ORC testing at 6 PM that day and continued for four consecutive days. By the evening of December 9, although a cough persisted, her other symptoms had significantly improved, so we paused testing. Her antigen test turned negative on December 10. A subsequent test on the evening of December 23 revealed that her pulmonary oxygen reserve capacity had returned to her pre-infection baseline level (as observed on December 6 before the weak positive result).Figure 1

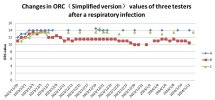

ORC Curves of Three Students After Respiratory Infection: In late November 2023, 4 out of 6 female students in my class's dormitory took leave due to respiratory symptoms, the specific cause of which was not definitively diagnosed. Three of these students, who were proficient in the simplified ORC testing method, verbally agreed to participate in a 5-month ORC tracking study, commencing on November 29.

Based on their ORC curves, their testing likely began after their lowest point of ORC. Students A and C's ORC values recovered to their baseline and stabilized within 4-5 days.

Student B's ORC value, however, after a brief return to baseline, began to fluctuate downward again and consistently remained at a relatively stable, lower level. Despite her subjective feeling of "recovery" and the absence of symptoms other than occasional coughing, her ORC value clearly indicated persistent impairment.Figure 2

This particular case highlights that even when an individual subjectively feels "recovered," objective ORC data can unveil subtle, underlying manifestations of post-infection sequelae. Student B's ORC curve serves as a potential quantifiable indicator for changes in post-infectious symptoms. (Notably, Student B's ORC eventually returned to the baseline levels of Students A and C by February 13, 2024, though this data is not depicted in the current figures, it can be provided.)

Potential Value of ORC Testing for ME/CFS and Long COVID Research:

Based on the cases presented, I trust that ORC testing is now more clearly understood. As a singular, objective, and precise indicator of pulmonary oxygen reserve capacity, it offers distinct advantages. For patients with conditions like Long COVID or ME/CFS who experience related symptoms such as fatigue, dyspnea, and exercise intolerance, ORC testing offers:

Condition Monitoring: Regular ORC testing (e.g., every other day or at longer intervals) can provide insight into the progression of their condition, even in the absence of a pre-illness baseline. An increasing ORC value suggests improvement, while a decreasing value may indicate worsening.

Treatment Efficacy Evaluation: Current evaluations of treatment outcomes often rely on subjective patient reports, which lack precision. The ORC test can provide a precise, objective, and quantifiable standard for assessing treatment effectiveness, aiding in the determination of the most beneficial therapeutic approaches.

As I've emphasized, converting subjective, ambiguous assessments into precise, objective quantitative metrics is an indispensable prerequisite for advancements in this field. While the ORC test may only address the symptom spectrum related to pulmonary dysfunction, it has the potential to be a transformative 'game-changer,' serving as an objective benchmark for various aspects of ME/CFS and Long COVID research.