AI Summary

Summary of the Study "DSM Disorders Disappear in Statistical Clustering of Psychiatric Symptoms"

The study "Reconstructing Psychopathology: A data-driven reorganization of the symptoms in DSM-5," led by Miri Forbes and colleagues, explores the quantitative structure of psychiatric disorders using a statistical approach that challenges traditional DSM-5 classifications. The research is set in the context of the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP), a model that emphasizes dimensional, hierarchical, and quantitative classification of mental disorders based on symptom patterns. The study's methodology is groundbreaking, utilizing a large, socio-demographically diverse sample of 14,800 participants who completed surveys based on DSM-5 symptoms. These symptoms were presented in a random order to minimize bias, and participants rated how true each symptom was for them in the past 12 months.

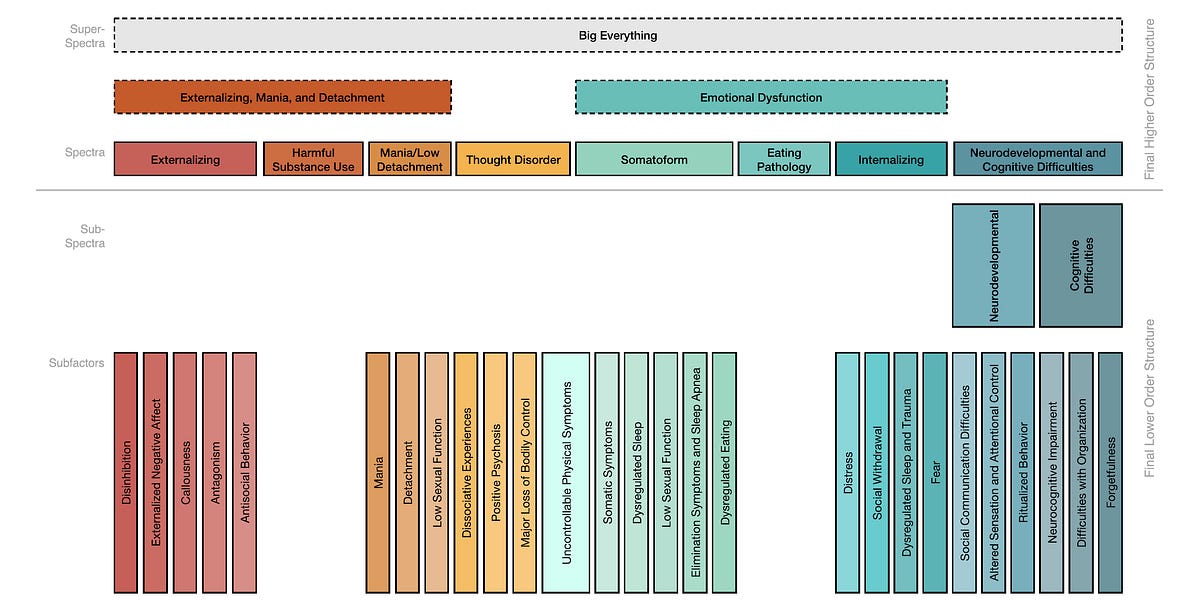

Through advanced statistical methods, the study identified 139 symptom clusters ("syndromes") and 81 solo symptoms. These clusters were subjected to hierarchical analysis to determine higher-order constructs, resulting in eight major spectra, such as Externalizing, Harmful Substance Use, Mania/Low Detachment, and Thought Disorder, with 27 subfactors. For instance, the "Internalizing" spectrum, which traditionally encompasses disorders like Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), was broken down into subfactors such as Distress, Social Withdrawal, and Trauma. Importantly, the results revealed that many classic DSM-5 disorders, including MDD, Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), did not emerge as distinct, coherent syndromes in the analysis.

The Disappearance of Major Depression and Other Disorders

The study's findings challenge the validity of traditional diagnostic categories like MDD, GAD, and PTSD, which failed to emerge as distinct clusters when subjected to statistical analysis. These disorders, as defined by DSM-5, appear to be heterogeneous in nature, with varying symptom subsets that do not correspond to a stable, identifiable syndrome. For example, while MDD is characterized by a combination of symptoms such as depressed mood, anhedonia, and changes in sleep and appetite, these symptoms were found to dissolve into more fundamental, statistically homogeneous clusters like "Distress," "Neurocognitive Impairment," and "Dysregulated Sleep." This observation raises the question of whether MDD, as it is currently conceptualized in the DSM, truly represents a cohesive disorder or simply indexes a broad, overlapping range of symptoms that vary across individuals.

Participants in the study demonstrated a wide variety of symptom combinations, making it clear that there is no single, unified symptom pattern that can reliably define disorders like MDD. For example, some individuals with MDD might present with depressive mood and suicidality, while others might experience irritability and sleep disturbances. The findings suggest that traditional psychiatric categories like MDD, GAD, and PTSD are, in fact, variable collections of symptoms that share certain core features (e.g., depressed mood for MDD, pervasive anxiety for GAD), but do not reflect fixed, stable conditions.

Implications for DSM and Psychiatric Diagnosis

The study's results imply that the symptom heterogeneity inherent in DSM-5 constructs may be problematic for accurate diagnosis. The lack of statistical homogeneity within the criteria for MDD and other disorders challenges the assumption that these disorders represent stable, discrete entities. Instead, they may reflect varying and overlapping symptom clusters that do not map neatly onto traditional diagnostic labels. As noted by psychiatrist Ken Kendler, while DSM criteria serve as an index for clinical depression, they may not fully capture the underlying, variable nature of depressive symptoms, leading to potential gaps in diagnosis and treatment.

Limitations and Future Directions

While the study provides valuable insights into the complexity of psychiatric disorders, there are important limitations to consider. The research relies on self-reported symptoms, which may not capture the full complexity of each individual's experience. Additionally, the study does not account for clinician observations or differentiate between symptoms caused by different factors (e.g., insomnia due to anxiety versus insomnia due to substance withdrawal). The time scale of 12 months used for symptom assessment may also overlook shorter-term variations in symptom patterns.

Forbes et al. themselves acknowledge the need for further research to validate these findings using alternative measures and time frames, as well as multi-method and multi-informant approaches. Additionally, future studies should explore how these results apply across diverse sociocultural contexts, given the potential for variations in symptom expression across different demographic groups.

In conclusion, the study by Forbes et al. offers a fresh perspective on psychiatric classification by challenging the stability and coherence of traditional DSM-5 disorders. It underscores the need for a more flexible, dimensional approach to understanding mental health that takes into account the complex, heterogeneous nature of psychiatric symptoms.