Chandelier

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Authors:

Published: 25 June 2025

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01172-3

www.nature.com

www.nature.com

- Maxime Taquet

- John A. Todd

- Paul J. Harrison

Abstract

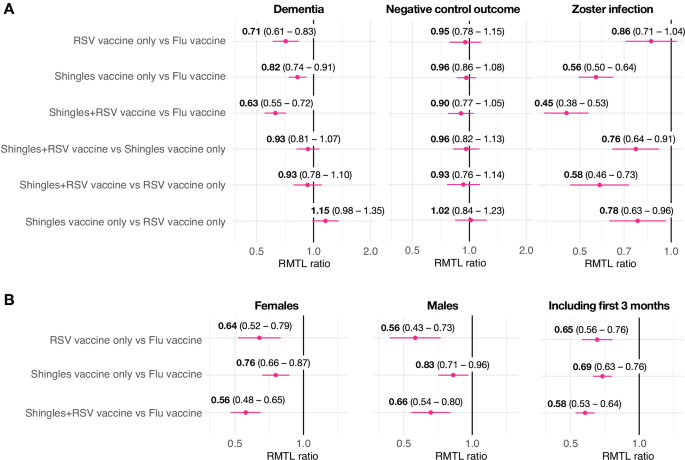

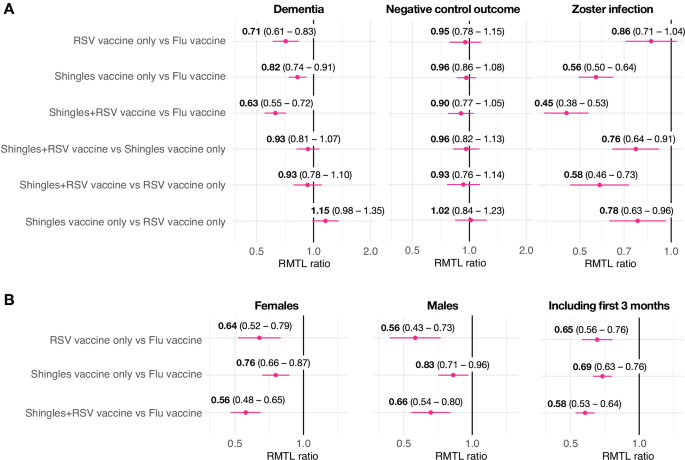

AS01-adjuvanted shingles (herpes zoster) vaccination is associated with a lower risk of dementia, but the underlying mechanisms are unclear. In propensity-score matched cohort studies with 436,788 individuals, both the AS01-adjuvanted shingles and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines, individually or combined, were associated with reduced 18-month risk of dementia. No difference was observed between the two AS01-adjuvanted vaccines, suggesting that the AS01 adjuvant itself plays a direct role in lowering dementia risk.Published: 25 June 2025

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01172-3

Lower risk of dementia with AS01-adjuvanted vaccination against shingles and respiratory syncytial virus infections - npj Vaccines

AS01-adjuvanted shingles (herpes zoster) vaccination is associated with a lower risk of dementia, but the underlying mechanisms are unclear. In propensity-score matched cohort studies with 436,788 individuals, both the AS01-adjuvanted shingles and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines...

Last edited by a moderator: