Dolphin

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

Individualized online exercise therapy aids recovery in pediatric long-COVID - Findings from an exploratory randomized controlled trial

Purpose To evaluate the feasibility, safety, and effectiveness of an individualized online exercise therapy (IOET) designed to improve physical capacity and quality of life in children and adolescents with long-COVID. Methods In this prosp...

Individualized online exercise therapy aids recovery in pediatric long-COVID - Findings from an exploratory randomized controlled trial

Sarah Christina Goretzki1Mara Bergelt2

Laurent Weis2

Rayan Hojeii1

Gabriele Gauß1

Miriam Götte1

Ronja Beller1

Sven Benson Prof3

Anne Schönecker1

Adela Della Marina1

Andrea Gangfuß1

Florian Stehling1

Christina Pentek1

Anna von Loewenich1

Tom Hühne1

Clara Held1

Sebastian Voigt4

Ursula Felderhoff-Müser1

Michael M. Schündeln1

Nora Bruns1

Katharina Eckert Prof2

Christian Dohna-Schwake1

Maire Brasseler1

1 University Duisburg-Essen, Children’s Hospital Essen, 45147 Essen, Germany,

2 IST University of Applied Sciences, Health Management and Public Health, Düsseldorf, Germany,

3 University Hospital Essen, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany,

4 University Hospital Essen, University of Duisburg-Essen, 45147 Essen, Germany

This is a preprint; it has not been peer reviewed by a journal.

Individualized online exercise therapy aids recovery in pediatric long-COVID - Findings from an exploratory randomized controlled trial

Purpose To evaluate the feasibility, safety, and effectiveness of an individualized online exercise therapy (IOET) designed to improve physical capacity and quality of life in children and adolescents with long-COVID. Methods In this prosp...

This work is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 License

Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the feasibility, safety, and effectiveness of an individualized online exercise therapy (IOET) designed to improve physical capacity and quality of life in children and adolescents with long-COVID.

Methods

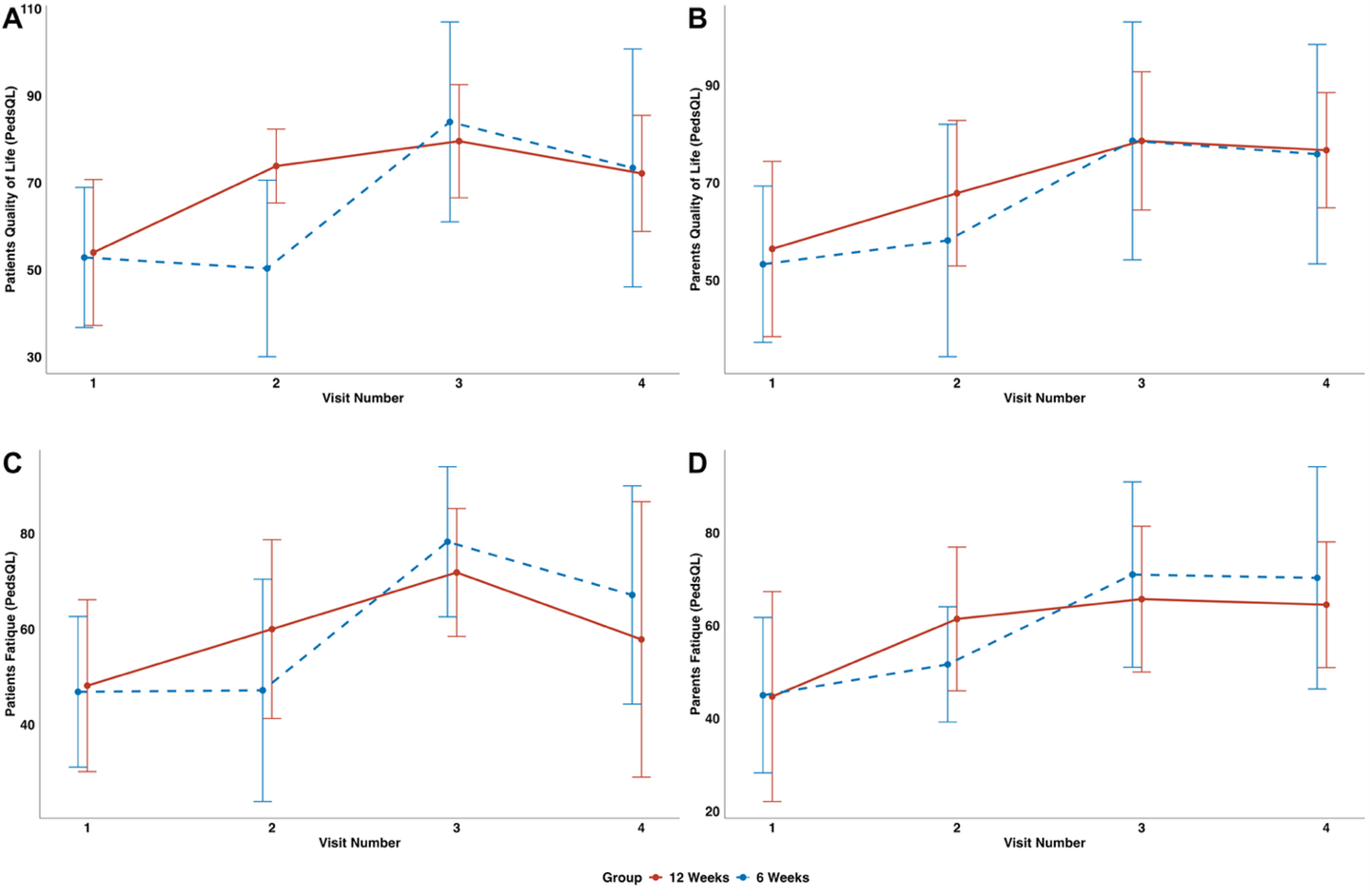

In this prospective, randomized, single-centre controlled trial, 14 patients aged 9–17 years (11 females, 3 males) with long-COVID (median symptom duration: 21 months) were assigned to either 6 or 12 weeks of IOET. The intervention comprised twice-weekly, telemedicine-delivered sessions tailored to individual ability and symptom burden, supplemented with diaries, activity trackers, and handouts for self-studies. Primary outcomes were physical performance (6-Minute Walk Test [6MWT], Sit-to-Stand Test [STST], Handgrip Strength Test [HST]). Secondary outcomes included school attendance, quality of life (PedsQL), physical activity, safety, and self-reported recovery.

Results

All participants showed clinically relevant improvements. In the 12-week IOET group, 6MWT increased from 396.0 m to 616.3 m, STST from 25.4 to 32.6 repetitions, and HST from 16.6 kg to 27.1 kg. The 6-week group improved comparably (6MWT: 429.0 m to 601.6 m; STST: 21.6 to 31.7; HST: 17.3 to 22.1 kg). School attendance rose from 58% to 97%, and PedsQL scores reflected improved quality of life and reduced fatigue. No adverse events or post-exertional symptom exacerbations occurred. Improvements persisted at 3-month follow-up, although some decline from peak performance was noted.

Conclusions

IOET is feasible, safe, and associated with improved physical function, reintegration in every day life and it’s quality in pediatric long-COVID. These findings highlight IOET as a promising rehabilitation strategy and justify larger multicentre trials to confirm effectiveness and define optimal programme duration.

Pediatric long-COVID

exercise therapy

fatigue

physical health

mental health

school participation