ME/CFS Science Blog

Senior Member (Voting Rights)

I’ve been reading this 2013 study by Friedberg et al. Chronic fatigue self-management in primary care: a randomized trial.

This isn’t a study of ME/CFS, but the paper claims that 39% of the 111 randomized participants did meet diagnostic criteria for CFS (Fukuda-criteria). I don’t think the diagnosis was checked or confirmed by a clinical investigation by the authors.

The possible inclusion of patients with ME/CFS seems problematic because the intervention in this randomized trial is very similar to the controversial type of CBT-used in research from the UK and the Netherlands. In what Friedberg et al. call Fatigue Self-Management (FSM) patients received two therapy sessions with a nurse. In the first session, participants were educated about “possible causal factors in […] CFS and stress factors and stress factors and behaviors that play a role in disturbed sleep patterns, post-exertional symptoms, and push-crash activity cycles. Persistent fatigue was explained as a symptom associated with doing too much or too little.” In the second session, unhelpful behaviors and beliefs about the illness were identified. Low functioning patients were assigned a regular sleep schedule and gradual low effort walking to increase tolerance of physical activity. This all seems highly problematic as the study included patients with ME/CFS.

The results were touted as positive, even though there were no objective outcomes in this unblinded trial. On the fatigue severity scale, patients in the FSM group showed a (statistically significant) larger reduction than patients in the control- and usual care group. But it seems like the control group (something called Attention Control which consisted of emotional support and training in symptom monitoring) didn’t actually work, as it performed similarly to usual care on the outcome of fatigue. Secondly, FSM did not outperform the other groups on secondary outcomes such as physical functioning (SF-36), depression or anxiety.

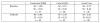

The most important flaw, however, seems to be the high dropout rate. The results and effect sizes cited by Friedberg come from the 12 month follow up. But at that time only 19 patients or 51% of the original number of patients randomized to FSM, provided data. Outcomes were also measured 3 months after treatment and at that point still 81% of the patients in the FSM group provided data. If one looks at the numbers (table 2) one can see that most of the decline in fatigue in the FSM group occurred between the 3 month and 12 month assessments. So this was many months after patients received the short 2 therapy sessions. It is very unlikely that this decline had anything to do with FSM and very likely that it was due to the high dropout rate (patients who did not improve might be less inclined to provide data 12 months after the treatment).

Unfortunately, I do not possess statistical skills, so I would like to ask the math magicians on this forum if it is possible to calculate p-values and effect sizes for the results for fatigue at the 3 month instead of the 12 month assessment. As far as I can see, this was not reported in the study, even though the raw data are available in table 2 (I tried to summarize it in the graph below).

All in all, there seems to be quite a lot of flaws in this paper. It might be misleading readers that the short fatigue self-management intervention was successful in patients suffering from chronic fatigue or CFS. If the p-values for fatigue at 3 month follow up, would turn out to be non-significant, it might be worthwhile to add a short Pubpeer comment about these flaws, even though the study is 6 years old.

This isn’t a study of ME/CFS, but the paper claims that 39% of the 111 randomized participants did meet diagnostic criteria for CFS (Fukuda-criteria). I don’t think the diagnosis was checked or confirmed by a clinical investigation by the authors.

The possible inclusion of patients with ME/CFS seems problematic because the intervention in this randomized trial is very similar to the controversial type of CBT-used in research from the UK and the Netherlands. In what Friedberg et al. call Fatigue Self-Management (FSM) patients received two therapy sessions with a nurse. In the first session, participants were educated about “possible causal factors in […] CFS and stress factors and stress factors and behaviors that play a role in disturbed sleep patterns, post-exertional symptoms, and push-crash activity cycles. Persistent fatigue was explained as a symptom associated with doing too much or too little.” In the second session, unhelpful behaviors and beliefs about the illness were identified. Low functioning patients were assigned a regular sleep schedule and gradual low effort walking to increase tolerance of physical activity. This all seems highly problematic as the study included patients with ME/CFS.

The results were touted as positive, even though there were no objective outcomes in this unblinded trial. On the fatigue severity scale, patients in the FSM group showed a (statistically significant) larger reduction than patients in the control- and usual care group. But it seems like the control group (something called Attention Control which consisted of emotional support and training in symptom monitoring) didn’t actually work, as it performed similarly to usual care on the outcome of fatigue. Secondly, FSM did not outperform the other groups on secondary outcomes such as physical functioning (SF-36), depression or anxiety.

The most important flaw, however, seems to be the high dropout rate. The results and effect sizes cited by Friedberg come from the 12 month follow up. But at that time only 19 patients or 51% of the original number of patients randomized to FSM, provided data. Outcomes were also measured 3 months after treatment and at that point still 81% of the patients in the FSM group provided data. If one looks at the numbers (table 2) one can see that most of the decline in fatigue in the FSM group occurred between the 3 month and 12 month assessments. So this was many months after patients received the short 2 therapy sessions. It is very unlikely that this decline had anything to do with FSM and very likely that it was due to the high dropout rate (patients who did not improve might be less inclined to provide data 12 months after the treatment).

Unfortunately, I do not possess statistical skills, so I would like to ask the math magicians on this forum if it is possible to calculate p-values and effect sizes for the results for fatigue at the 3 month instead of the 12 month assessment. As far as I can see, this was not reported in the study, even though the raw data are available in table 2 (I tried to summarize it in the graph below).

All in all, there seems to be quite a lot of flaws in this paper. It might be misleading readers that the short fatigue self-management intervention was successful in patients suffering from chronic fatigue or CFS. If the p-values for fatigue at 3 month follow up, would turn out to be non-significant, it might be worthwhile to add a short Pubpeer comment about these flaws, even though the study is 6 years old.

Last edited: